Are We Rational? The Decoy Effect and Social Information

Our heuristics are smarter than you think

Please hit the ❤️ “Like” button at the top or bottom of this article if you enjoy it. It helps others find it.

A man takes his seat at a restaurant he isn't familiar with.

"Will you be having the steak or the salmon?" the waiter asks.

"I'll have the steak," the man replies.

"Very good, sir. Oh, I forgot: we also have lobster. Would you like to change your order?" the waiter asks.

"Yes," the man says. "In that case I'll have the salmon."

This sounds like a bad joke (because it is). But let me dissect it, since that always makes jokes better.

It seems ridiculous that the man would change his order like this. If he preferred the steak to the salmon before, adding another option shouldn't change that preference. So the man is acting irrationally.

Or is he? (Geeze, this whole opening is the corniest hook I've ever written)

Here's a plausible story of what happened: The man loves salmon, but only when it's very fresh. In this part of town, it's rare that a restaurant would have fresh fish. Steak is a much safer option. But when he hears the restaurant also has lobster, this gives him more information: a place that has lobster takes seafood seriously, so they're much more likely to have fresh salmon.

That extra information he gained from hearing about the lobster changed his mind.

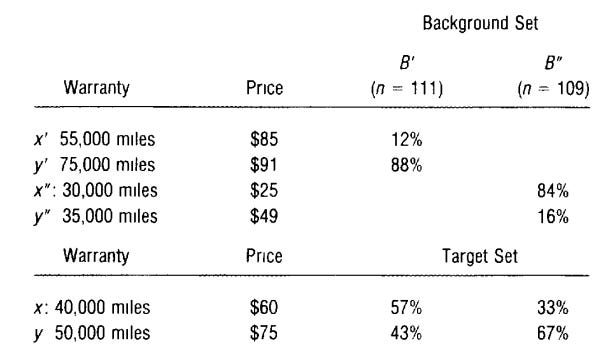

Many classic examples of irrationality in the lab have this kind of flavor. For example, in a classic study of decision-making, researchers presented participants with two choices about car warranties. In the first (the "Background Set"), there either was a small difference in price between the warranties and a large difference in the covered miles, or there was a large difference in price and a small difference in the mileage covered by the warranty.

When it came time to choose between two options with a moderate difference between both mileage covered and price, participants that had been exposed to the condition where the mileage was "cheap" tended to opt for the lower-price; they weren't as willing to pay for mileage. Those exposed to the condition where mileage coverage was expensive, however, tended towards the higher mileage option.

This makes sense. For those participants where the first set of choices indicated mileage coverage is usually very expensive, the moderate increase in price for an increase in covered mileage seemed like a good deal. For those who the change in warranty mileage didn't lead to a large increase in price, it makes sense that they would consider mileage "cheap" and therefore wouldn't spend the extra money for a moderate increase in it.

We use the information we glean from the options on offer. It provides social information: how much does the price-setter think these things are worth? When we have uncertainty about how much we should pay for something, it makes sense to use this additional information to inform our choices.

This is all totally rational, driven by our uncertainty about how much something is worth.

Unfortunately, marketers are extremely aware of the power of social information. The Decoy Effect is where a product is intentionally priced to nudge us towards a more expensive option by exploiting our use of the social information in pricing.

In the image's example, the pricing of the "medium" coke at $3 gives the social information that $3 for a medium coke isn't a ridiculous price—so $2 for the large coke is a great price! While in the real world it's rare for pricing to be this blatant, the general effect is something marketers know about and use in subtler ways. Marketers often use other methods to convey similar social information—like claiming something is 20% off (when it always is).

Despite being something marketers can exploit, it's hard to say this is irrational behavior on the consumer side. It makes sense that we are often uncertain about how much things are worth and that we would use clues like the pricing of other products to figure that out.

This is one feature that makes rationality really hard to study in the lab. Decision-making experiments usually involve giving individuals weird choices they don't face in real life. Giving a strange choice introduces a level of uncertainty to participants, and the different options on offer convey social context about what the researchers consider reasonable trade-offs.

The Bias Bias

There are plenty of other areas where our supposed irrationality actually might be smarter than it seems.

For example, the supposed impulsivity of children in the infamous marshmallow task is partially because of smart reasoning about the stability of the environment. Kids that have more reason to expect an unstable environment, because of an experimental manipulation teaching kids the experimenter is not reliable or because of their home economic environment, are less willing to wait. Instability in the environment means there's a greater chance they won't get what they were promised—and might have what they've been given taken away.

Similarly,

has pointed out that the so-called confirmation bias is actually an efficient strategy in information seeking.We're smarter than many popular depictions show. You can't really publish a study that just shows people making a rational decision, but any seeming deviation from rationality can by itself be published—and often garners much more interest from the popular press. I know this from first-hand experience!

Fittingly, this means there's a bias in the picture we get of cognitive biases.

The Rational and the NPCs

My point is not that we're optimal decision-makers, rational in all areas, but that decision-making is nuanced, and this makes it often difficult to study in the lab. It isn't always easy to figure out what rational looks like in a given context. The context of a psychology lab is weird—it's unfamiliar, you know you're being studied, and the questions you're asked are often not like anything you run into in the real world. This introduces some level of uncertainty—exactly the kind of situation where people would reach for additional information sources, like social cues.

The picture we often get from popular science write-ups is that people have tons of random unrelated irrational biases. I suspect many people read that stuff and get the impression that they rise above that, that the "Sheeple" or "NPCs" are stuck with biases, but those smart enough to do things like read about biases have the cognitive horsepower that lets them avoid heuristics altogether and act as beings of pure reason.

The full picture is more complex. A lot of the heuristics and biases we read about are good strategies that just look weird when studied in certain contexts in the lab. We're reasoning in ways (often unconsciously) that are far more clever than you would think. There isn't such a thing as giving up heuristics for pure reasoning—we're all limited beings using different strategies and information in the real world under different constraints. More on that in a future post.

Please hit the ❤️ “Like” button below if you enjoyed this post, it helps others find this article.

If you enjoy the newsletter, consider upgrading to a paid subscriber to support my writing.

Thanks for this useful corrective. The example that always got to me was the one where people conclude that it's more likely that Barbara, after her activist youth, is a bank teller and a feminist than that she is a bank teller. In an everyday reasoning sense, it IS more likely, even though statistically, that makes no sense. But when I learned that the only group of people who get the Wason Selection Task (knowing how to disprove a conditional) are philosophy graduate students (as I was at the time), that cemented my sense that the critical studies of human rationality were probably looking for the wrong thing. If it means that your thinking doesn't always conform to the canonical rules of logic, so what?

This post makes me consider the possible pitfalls of teaching people to recognize cognitive biases in each other. I've had a nagging suspicion that tweets and listicles that list the top cognitive biases and encourage viewers to study them intensely and be extra vigilant about defending themselves against them sends the wrong message: it encourages viewers to pass judgment on those they know nothing about. Sure, there may be times where you need to challenge your own cognitive distortions, but not everyone around you needs you to challenge their supposed distortions for them! I think rather than immediately labeling someone as irrational first, we need to be curious and ask non-leading questions first, THEN we can analyze them.