Brainrot, Screen Addiction, and Late-Stage Capitalism

The Merchants of Pessimism are selling simple fictions to cash in on our negativity bias

Please hit the ❤️ “Like” button at the top or bottom of this article if you enjoy it. It helps others find it.

Our brains aren't rotting, we're not all in the collective throes of addiction, and society at large isn't about to collapse under late-stage capitalism. But if you've spent any amount of time on the internet or even—gasp—talking to people in the real world, you've probably encountered some dire opinions about the state of the world.

These sorts of sentiments are widely shared on social media, espoused in books that sell millions of copies, talked about on podcasts, and so on. But many of these narratives aren’t just wrong—they’re misleading, self-serving, and actively distort how we understand modern life.

Laziness Does Exist

Devon Price holds a PhD in social psychology, so you could be forgiven for thinking he would be a reasonably careful source. When I read his book, Laziness Does Not Exist, I expected an interesting take on laziness not being the right way to think about motivation. Instead, it's about blaming any behavior perceived as laziness on us all being systematically overworked.

It's certainly the case that many people are overworked, and it's wrong to write off those who are overworked as "lazy" for not doing more.

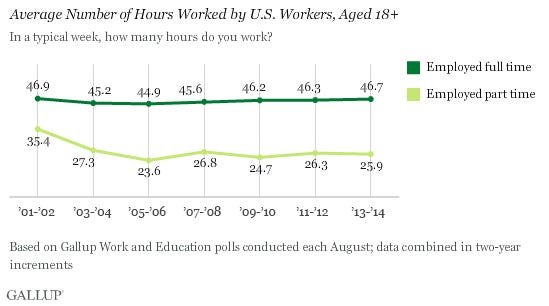

But the book goes much further than that, attempting to draw a picture of a world being crushed by capitalism, where increasing amounts are asked of us and then we're chastised for being lazy when we can't keep up. The trouble is that even just looking at the sources cited in the book itself undermines its central claims. To take one example, we're told on page 77: "In the past two decades, the average workweek has gotten longer and longer". Here's the figure from the source Price cites:

This is the supposed evidence that the average workweek (in the US) has gotten "longer and longer" the last two decades. If you're confused, you're right to be. It's hard to imagine how one would think this figure, showing a flat line for full-time work and a big decrease for part-time, supports the claim that the workweek has increased. I think what happened here is Price made an assumption that the average used to be working 40-hours, read the title of this article, 'The "40-Hour" Workweek Is Actually Longer', and decided that meant hours have increased. In other words, Laziness Does Not Exist is a great example of lazy research.

But it also points to a general trend in this kind of pessimistic view of the world's trajectory that I've noticed: imagining a much rosier version of the past, comparing it to our current reality with all its imperfections, and concluding the past was better.

The article Price chose to cite only has data going back to 2014—perhaps it's changed since then and Price just used the wrong article as a source? Here's a more recent article from the same organization Price cites (Gallup), showing recently there has been a decline in hours worked:

This all aligns well with other sources of data reporting, broadly, flat or declining hours worked across various countries and time periods.

Of course, some people work more than they did decades ago. There are certainly people who are overworked. But by claiming the workweek in general has trended towards being longer, Team Pessimism is divorcing themselves from reality and obscuring who really needs help.

Anna Lembke for the pessimism rebound

In case you're worried my statements above paint too bright a picture of the world, fear not. Anna Lembke in her bestseller, Dopamine Nation, tells us it's actually a bad thing that people have more leisure time! Lembke claims that since people have more leisure time now, there is more time to engage in activities that are addictive.

What kind of horrible addictive activities? According to Lembke, literally anything pleasurable. Also anything painful, since you might get addicted to the "high" after the pain. So please only engage in very neutral activities.

Lembke's go-to example from her own life of a horribly debilitating addictive activity is reading romance novels. She enjoyed doing this so much she started to (gasp) read them in her downtime at work. She describes romance novels, along with video games, as drugs. Not like drugs. As drugs. She justifies this thinking with a wild overapplication of a simplified model of the reward system in the brain, where pleasure and pain are opposite sides of a scale and the scale always comes back into balance. Rather than unpacking all the problems with this, let me just say that while simple models are great for understanding simple phenomena, they are not great to apply to something as complicated as all of motivated behavior.

Behavioral addictions exist—gambling is the quintessential example. And we certainly form habits around using various technologies that can be hard to break. But to paint them as addictions and apply a simplistic model of pleasure to thinking about the range of activities isn't helpful—it puts things so wildly out of scale with reality. Addiction has specific medical criteria that are far more stringent than "once I stayed up late scrolling my phone or reading a book". You don't have to worry that because you're enjoying something you'll become debilitatingly addicted to it. It's okay to enjoy some parts of life.

Lembke's views may seem like an insane fringe belief. They should be! Yet Dopamine Nation has sold millions of copies. It struck a chord.

I suspect the chord is because she takes aim at technology, saying things like "the smartphone has become the modern-day hypodermic needle". There's an anti-technology zeitgeist that she's tapped into, allowing her to smuggle in some of her wilder ideas comparing reading books to drug addiction.

Brain Rotting Technology

The anti-technology sentiments so popular on social media are understandable. We've all had the experience of procrastinating on something by endlessly scrolling on our phones, or trying to work on something but constantly finding ourselves pulling out our phone instead.

In yet another incredibly popular book, Deep Work, Cal Newport claims that technology is doing irreparable damage to our brains. The instant gratification and shallow engagement with content on social media rots our brains, robbing us of our ability to pay attention and engage in deep work.

The trouble is, Newport’s central claim—that our cognitive capacities are being eroded—rests more on intuition than on evidence.

There's plenty of associations—some studies people love to point to show lower grey matter in the brains of those who use phones heavily. But this is a simple "correlation is not causation" issue. We already know those who have less grey matter in regions associated with focus and self-regulation engage in more phone use, so a simple explanation of the association is that the brain and behavioral differences we see cause more problematic phone use, not the other way around (see Dean Burnett's article on this issue). But since it makes a more dramatic story to say phone use causes a reduction in grey matter, that's what people go around talking about.

What makes the story seem plausible is that we feel ourselves get distracted by our phones. It might even feel like we have less of an attention span than we used to. But there's a simple explanation for this. Phones are pretty much the perfect procrastination devices. We can pull them out and in a second pull up an endless feed of small bites of entertainment personalized to our interests. There's just no friction to using them, which is both their great strength and what makes them such distractions. When we run up against something we don't want to do—it would require some mental effort or just be otherwise unpleasant—we are mentally comparing whether we want to do something difficult to pulling out our phones for something enjoyable and very easy. We'll often take the easy path. When notifications are on, we at any moment might receive an indication of something of interest going on—breaking up our focus.

It's easy to misinterpret attention problems. We can't actually multitask. People are weirdly bad at realizing how poorly they perform when attempting to do two things at once. Having our attention pulled away by a quick check of a feed, notifications, or anticipation of a notification—it makes sense that all of these can reduce our attention while we're engaging in these activities. There's no need to assume an additional decline, over and above the in-the-moment distraction, to our cognitive abilities.

The distracting nature of phones is a real issue! But it's easily mitigated: just put the phone away or turn on "do not disturb" when you want to focus. If you don't want to lay in bed scrolling on your phone in the evening or morning, add some friction to using it—leave it outside your room when you plan on sleeping. These are easy, common sense and incredibly effective ways to deal with phones.

That's not the story you'll be told by Cal Newport or Anna Lembke, though. According to Team Pessimism, phone use is dangerously addictive and wreaks havoc on your brain, causing irreversible harm to our ability to focus. If you think of phones like a needle drug, it doesn't make sense to just turn the needle drug on "Airplane Mode" when you want to get work done.

These anti-phone sentiments are the latest moral panic. Just like the concerns about violent video games in the 90s, Dungeons & Dragons in the 80s, cannabis in the 70s, "TV zombies" in the 50s, and so on. All of these were overblown concerns based on vibes instead of evidence.

The language of addiction and brainrot focuses us on the wrong things. Instead of being a useful device that we should be mindful of, people think of phones as inherently harmful, as necessary evils they have to use. But the truth is they're just devices that bring a lot of benefits. I can pull out a phone and capture a picture of my kids while they're playing, share that with my parents who live in another country, increasing the closeness we feel despite being geographically far away. I can instantly look up any information, make friends with people on the other side of the globe, take care of small tasks, get directions to anywhere I could possibly want to be. Phones are great. Recognizing the actual downsides, not the made-up ones, allows us to reap the benefits while mitigating the downsides.

Angels and Devils

"Late Stage Capitalism", "brain rot", and "dopamine addiction" are all pithy terms giving us a simple and evocative image of the world.

In psychology, there are two related phenomena called the Horns and Halo effects—people or brands that we see as good in one way, we tend to view positively in other domains as well. For example, people who are attractive are typically judged to be more competent and personable based only on their appearance.

It's cognitively easier to think of something as all good or all bad. Seeing society as a mix of progress and worrying developments is hard. Thinking of technology and "screens" as not a necessary evil, but a mix of good and bad that we have to consciously make decisions about is hard. It's easier to focus on a grim but one-dimensional version.

We have a negativity bias: we pay more attention to bad things and interpret the world more dimly than it deserves. When we combine our preference to paint things all one color with our tendency to see things negatively, we paint everything some drab yellow-green called "Everything Sucks".

The world isn't all sunshine and rainbows. There are certainly worrying things about overly capitalistic culture, or with frictionless but empty entertainment. Recognizing the actual downsides—rather than the imagined ones—lets us use technology on our terms. We shouldn't look at the bad and decide everything is bad—especially since so much of the purported bad is just plain made up.

Please hit the ❤️ “Like” button below if you enjoyed this post, it helps others find this article.

If you’re a Substack writer and have been enjoying Cognitive Wonderland, consider adding it to your recommendations. I really appreciate the support.

I think this is overly rosy, particularly the phone stuff. I think I buy the potential explanation that people were always bad at focusing on things and the phone is a perfect distraction and scapegoat. But the constant availability of a distraction machine seems pretty bad in and of itself, no? If we think of our intelligence/mental capabilities as a combination of our brains and the things we have available to us, something that is designed to ping us then suck is into an endless scroll seems like it could very easily reduce our attention span when we have access to it (which is almost all the time) could produce something that feels to the user very much like brain rot, even if it is not literally rotting our brains.

In my personal life, I and basically everyone else I know has put limits on various apps because we don’t like how we behave with them. I think that is different from just putting the phone in another room when we sleep. It sounds like you have an uncommonly good relationship with yours!

I wholeheartedly agree with your thoughts here. Technology, social media, etc. isn't such a bad thing as much of society has made it out to be. Though, the negative perception by society is totally understandable.

The internet ecosystem has strayed so far from its philosophical and foundational origins that most of the original optimism for humanity's future in relation to the internet has waned by now. The internet was originally supposed to be largely decentralized, avoiding placing much power in the hands of a small number of entities. Unfortunately, this is progressively becoming less the case today, as companies like Meta, Google, etc., buy other social media platforms for themselves, thus taking control of their entire user-bases. It doesn't help that social media sites are generally centralized around single corporate entities that have full control over the platform; this was never supposed to happen. Although one could argue that the internet is still decentralized, is that really the case though? If discontinuing the use of one platform from one company can isolate you from so much of society, it's too centralized.

It also doesn't help that internet platforms started to be designed to psychologically exploit their users through short, attention-grabby forms of content. The sheer volume of such fragmented and disordered units of information has really forced all our brains into maximum overdrive; it's no wonder people are generally much more anxious these days. As if that wasn't bad enough, social-media "algorithms" are further optimizing the amount of junk that can be shoved into our brains. This is why I'm so glad that platforms like Substack, among others, still exist and are becoming increasingly popular. Although far from perfect, they are a net-improvement to the status quo. The longer-form content, which requires focused and sustained effort on the part of both the creator and the consumer, is such a refreshing break from the norm.

Personally, I've been musing over some concepts for a new type of social media that is geared toward bringing the internet back to its original philosophical underpinnings, as well as gravitating back toward the longer-form content that didn't fry our brains. I may actually start developing it soon as well; we'll see. I really would like to return to those early days of the internet's expansion, which were characterized by optimism for the future; I do genuinely believe it is possible if we try.