Could your green be my red?

Short answer: No. Long answer: Not really, but let's talk about bats a bit

Please hit the heart “Like” button at the top or bottom of this article if you enjoy it. It helps others find this article.

Anyone who has philosophical leanings (or has smoked a joint) at some point has thought: when you see colors, are they the same as the colors I see? When you see red, do you experience the same red I do, or some other color (like my green)?

In the old-timey words of John Locke:

Neither would it carry any Imputation of Falsehood to our simple Ideas, if by the different Structure of our Organs, it were so ordered, That the same Object should produce in several Men’s Minds different Ideas at the same time; v.g. if the Idea, that a Violet produced in one Man’s Mind by his Eyes, were the same that a Marigold produces in another Man’s, and vice versâ.

—John Locke, presumably after smoking a fat blunt

Since we both would have grown up having "the color of strawberries" labeled with the word "red", we would both react to "the color of strawberries" by saying "red" even if we were seeing/experiencing a different color. We could never know if we were truly seeing the same color. Or could we?

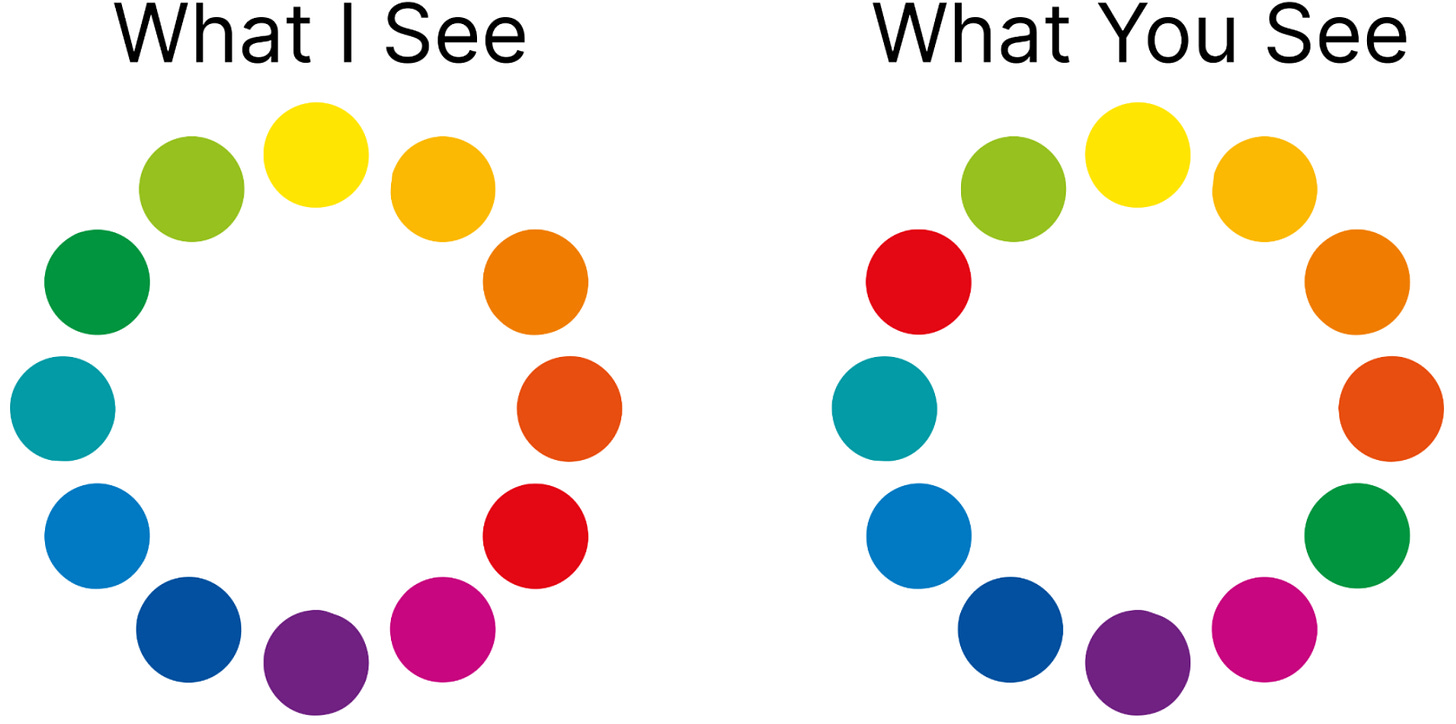

Imagine the most literal form of this thought: your green is my red, with no other changes. When we look at a color wheel, here is what we might see:

I've intentionally done the dumbest possible swap here, changing pure green with pure red and not changing anything else, even the very reddish orange on your color wheel.

This is to illustrate a point: colors have relationships to each other. We can't just take one particular color and swap it with another.

On your color circle, red and green stick out. Orange is a mix of yellow and red. If we only change your pure red to green, there would be a sharp discontinuity as we move from shades of orange to red. We would move from orange to slightly more reddish oranges until—POP—suddenly you see green. You would notice this and likely talk about this strange feature of red seeming out of place, and everyone would think you're weird.

But this isn't what we meant when we thought of your green being my red—we wanted the difference to be something we couldn't detect by your reactions to color. A difference only in our private experience.

For that, we'll have to change more than just green and red.

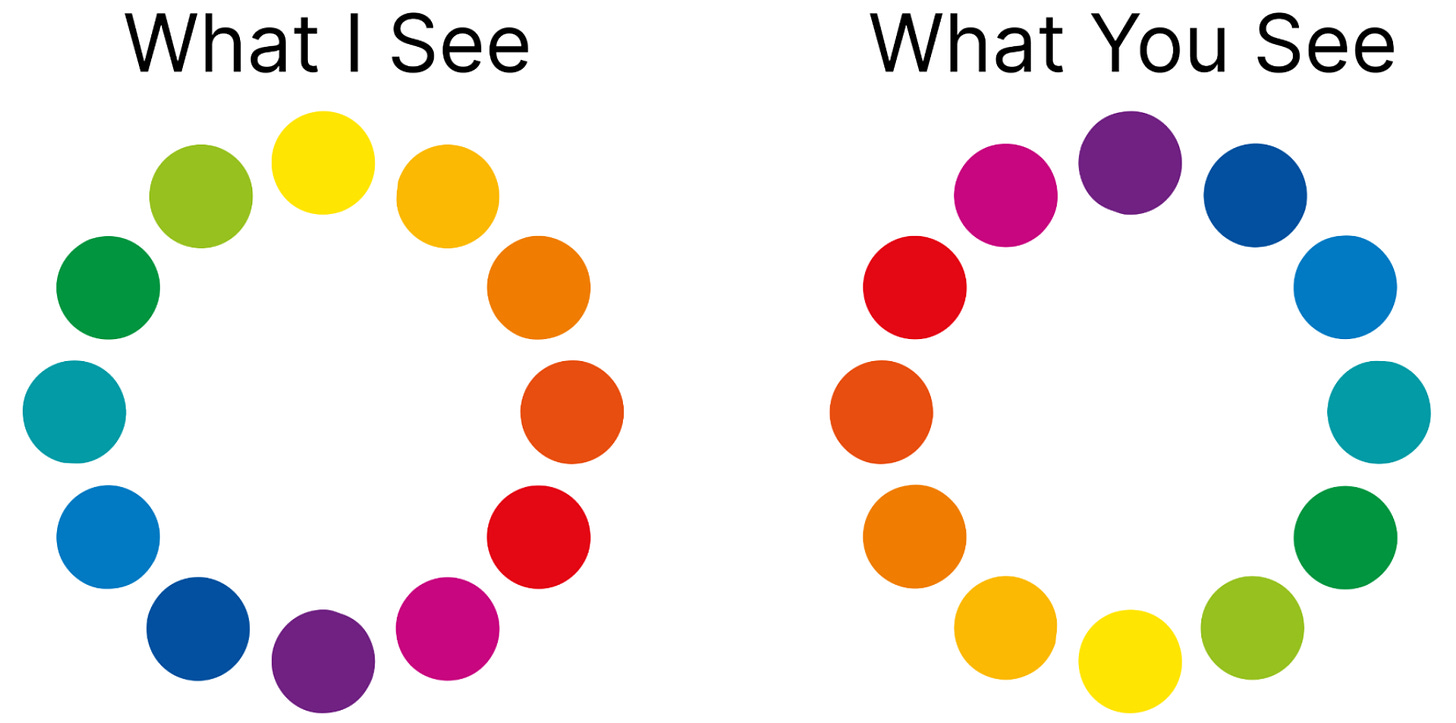

A more plausible change is rotating the whole hue space. We would end up with something like this:

Now my red is your green, and we've also had to change the rest of the hues—blue/purple have swapped places with yellow/orange. Nothing is obviously wrong with this at first glance.

Nothing is wrong if we're just looking at hues, that is. Unfortunately for us, color comprises more than just hues; it also has saturation and lightness. When we add those to our picture, things get weird:

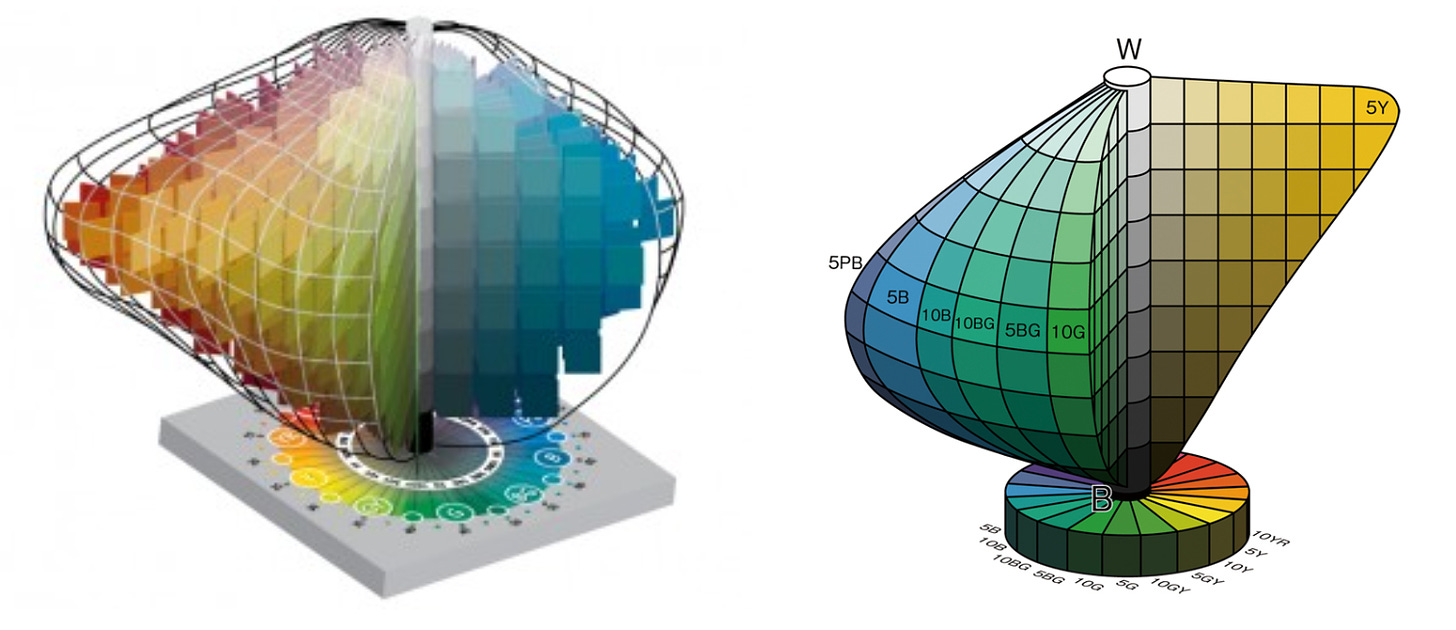

This space is irregularly shaped. The weird shape is because of asymmetries in what we humans perceive. For example, we can differentiate more greens than we can yellows. As we move down in lightness, yellow quickly becomes an indistinguishable brown, whereas we can perceive many shades of green-brown.

A simple rotation in hues wouldn't work for our purposes—if we rotated this space to make my green your red, you could differentiate colors in a dramatically different way than other humans. Again, this would break the rules of what we're trying to do—we want an undetectable change to private experience, and instead you're now able to differentiate a bunch of shades of yellow other humans can't (and unable to differentiate a bunch of shades of green others can).

You could instead rotate the space and say that you differentiate as many shades of red as I do of green, but now we're forced to assume not only is my green your red, but your red (and yellow and other colors) are fundamentally different from mine: when your yellow gets darker, instead of just turning to brown, you have a rich set of yellow-browns unlike anything I have (or can) see or experience. I no longer can picture in my mind's eye what your color experiences are because they don't have a mapping onto my color experiences. You've had to add new colors.

You could try to imagine more sophisticated transformations, or maybe moving out of color space to look for other experiences we could simply swap. But the game isn't fun anymore—the simple change we initially envisioned doesn't work, and it's not clear we could come up with a change that makes sense. So let's move onto something more fun: neuroscience!

The shared basis of color vision

The idea that our color experiences could be swapped or inverted comes from an interesting tension in our intuitions: We simultaneously feel like color is something objective (colors are out there, properties of objects) and subjective (it's hard to describe the experience of seeing a color, you just have to experience it).

I think there's something to this tension.

It's not literally true that colors are out there (I'm not going to justify this statement as much as one could, read Outside Color for a more formal philosophical treatment of color ontology—be warned it's boring).

But it is true that we all have similar perceptual systems that allow us to discriminate between wavelengths of light in similar ways.

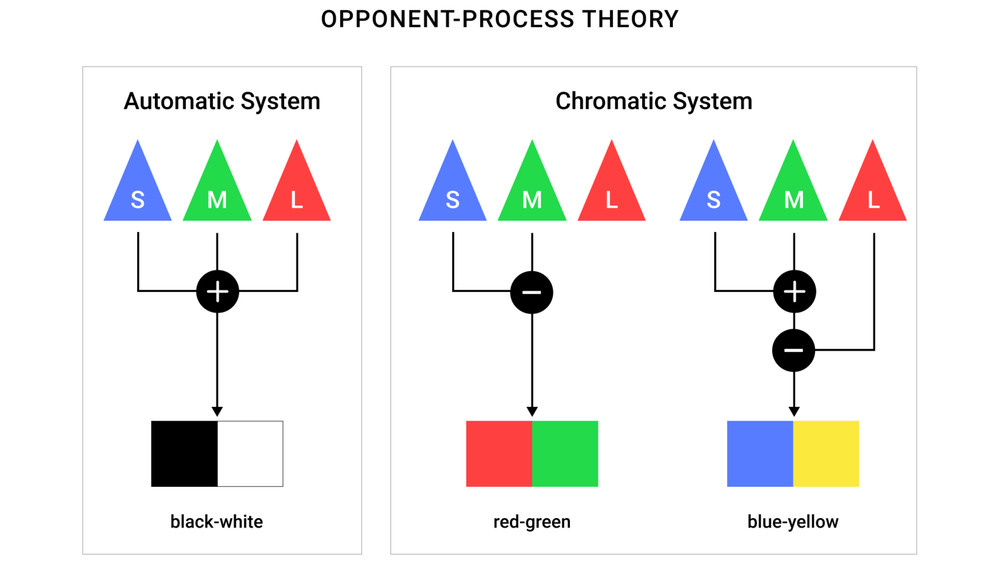

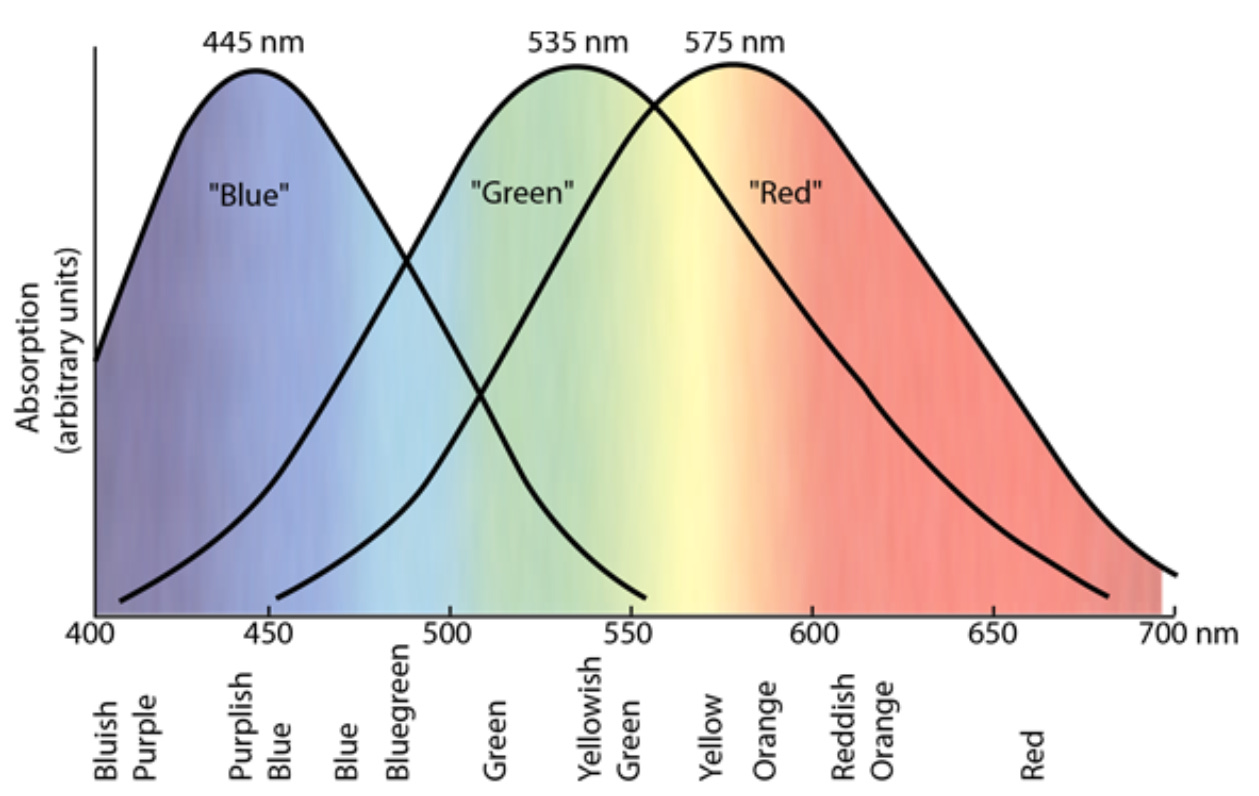

Most of us (I'm excluding the color blind here and the potential tetrachromes) have three kinds of cones in our retina that respond to different wavelengths of light: "Blue", "Green", and "Red" cones. We also have rods—they're able to detect light at much lower levels but don't distinguish wavelengths, which is why in low-light our vision seems to lack color.

Note that from a single type of cone, you aren't able to figure out what color is being shown—the "Red" cone, for example, has the same response for some shades of green as it does for some reds. Only by looking at the "Green" as well can we tell what's going on—if "Green" is not active but "Red" is, we know we're in the >600nm range that we perceive as red.

Our nervous systems integrate the information from these three cones in similar ways. One popular theory of how it does this is the Opponent Process Theory, which claims we combine the information from the three types of cones into three other signals: "Red versus Green", "Blue versus Yellow", and "White versus Black" (this last one being luminance).

This gives us the three dimensions of color seen in the Munsell color solid above, and when the properties of the signals are taken into account (like the fact that the "Green" and "Red" cones' range squish up against each other), it seems to match the asymmetries of the Munsell colors pretty well.

(As an aside: the Opponent Processing Theory is probably at least partially wrong, but I think it's a warranted simplification for our purposes here).

Our shared visual processing systems seem a good explanation for why color seems objective and third-person: We all are using the same wetware to look out into the world.

The Public and the Private

When we imagine being able to change my red for your green, the idea is that we can compare these experiences. We can pull out my experience of red and, in some objective sense, check it against your experience of green. But as we've seen with the color solid, these experiences aren't isolated things. They're embedded in a wider space with relationships that need to be preserved. When you and I share that space and the relationships, we can share the experiences in it.

It's a common trope that we can't describe what it's like to see red. But this is obviously wrong. I can say "it's like a darker, more saturated pink". Or "It's like a combination of yellow and magenta". Of course, if you don't have those references in color space, it becomes harder to describe. Having close referents makes it easier for me to get you to imagine a color—or any experience.

A good way of thinking about how we imagine color comes from studies of mental imagery: When we imagine something visual, our visual cortex activates in a similar way to if we were actually seeing that thing. Our brains are using the visual system to simulate what it would be like to see that thing.

I suspect this goes beyond just the visual system. When we try to imagine what it is like to be something, we are trying to simulate that experience on our neural wetware. The better we can simulate an experience (visual or otherwise), the better we're going to feel like we know what it is like. If we've experienced something similar before, we can call to mind that experience, tweak it, and simulate what it would be like for us to have experienced it.

We share more than just our visual systems. In the grand scheme of things, we humans are pretty similar to each other—for example, we're wired up to have similar emotions, giving us a similar "emotion space", like the color space we talked about above.

Let's say you wanted to describe to a friend the experience of reading your favorite publication, Cognitive Wonderland: "It's like Hemmingway's prose combined with Feynman's wit and brilliance and Carl Sagan's wonder of science, all enhanced by picturing the author's dashing good looks." (As an exercise, I recommend you try this exactly as described—it will improve your understanding of consciousness, I promise).

Your friend could imagine this by drawing on their past experiences of reading in general and reading great prose combined with brilliant ideas specifically. The experience they imagine might be a pale comparison to the sheer ecstasy of the genuine experience, but it should get them in the right ballpark.

But what if we tried something harder, like imagining what it's like to be a bat? Bats fly, hang out upside-down, and navigate by echolocation. It's radically different from our experience in all kinds of ways.

It's not straightforward to simulate this experience. I can make analogies—maybe having echolocation would be like me getting stop-motion images of what's around me. And flying is kind of like running, but, y'know, with a vertical component. But these are rough analogies. We can't simulate echolocation.

We can still understand bats and their consciousness—we can study their brains and actions, understand the mechanisms and limits of their perception.

Just as our color experiences inhabit particular points in a color space that bears a particular shape, with each point in that space having relationships to the other points, we can think of a bat's experience space—the large, many-dimensional space of all possible experiences a bat could have.

If we had a fully mapped out "bat experience space", where we understood the contours and relationships of each possible experience—would such an explanation be "leaving something out" if we couldn't imagine what it's like to be a bat?

In a sense, yes. We can't simulate what it's like being a bat because we can't put our brains in the states of a bat's—because we don't have the same kind of brain. A science of bat consciousness can't stimulate the parts of our brain to give us the experience of what it is like because we don't have those parts of the brain. There's no experience that a bat has that could be pulled out and examined next to ours.

There's nothing mysterious about this. We don't expect a book on how to play tennis to come with a built-in process for stimulating our motor cortex to develop the same connections playing tennis would so that when we're done with the book, we can stand up and be perfect tennis players. But the book can still be a perfectly good explanation of how playing tennis works. Similarly, we shouldn't be worried we can't have a science of consciousness because such a science couldn't transform our brains into those of bats and stimulate all of the experiences bats have. The science can still be a full and complete explanation.

There's something to be said here about empathy. When we imagine what it is like to be someone else, we are assuming their mental space is analogous to ours. While we humans share a lot, we're also all unique. I can try to understand your traumatic childhood or the passion you feel for a political issue, but I do so by trying to map your description onto a point in my mental space. That mapping is always going to lose something in translation.

But our ability to simulate different experiences is enhanced as we go through life and have a wider range of experiences. We explore more of our "human experience space" and have more land-marks in it for imagining what different experiences would have been like.

Our "human experience spaces" aren't all the same. Every person's loves and hurts are all different and in some sense incomparable, embedded in our mental spaces that makes each of us unique. But as we mature and learn, with a bit of effort, we can better know what it is like to see the world through each others' eyes.

Please hit the “Like” button below if you enjoyed this post, it helps others find this article.

If you’re a Substack writer and have been enjoying Cognitive Wonderland, consider adding it to your recommendations. I really appreciate the support.

This question has always brought up fascinating implications about the seemingly private nature of our consciousness. Such a thorough understanding of the mechanics of perception really seems to undermine the idea that your conscious perception is completely personal and ineffable. It can be broken down piece-by-piece and examined — compared against the larger backdrop of human mental experience.

And, as you say, this ought to grant us quite a bit of empathy, knowing that so much of our experience is shared and explainable. Something that feels so personal and private and indescribable is actually quite universal.

Fascinating piece!

I think the details of how my brain processes sensations is a little different from yours. We probably don't see red and green differently but I have a brain tumour and I do smell scents that you don't smell and vice versa. Ronaldo and Messi are able to track a football in ways that I am not able. Da Vinci sees the world a little differently too. There's probably no one that sees the world exactly the way that I do but there's also no one that sees it completely differently. It's a spectrum.

Bats too.

Most bats have sight that is worse than ours. Some a little, some a lot. None are completely blind though. It's a spectrum. This American Life has an episode about a blind man, Daniel Kish, who has learned to echolocate by clicking. He's blind like a bat but he echolocates like a bat too. Is he completely the same as a bat? Or completely different? Or are they both on the same spectrum that we are on?

I think we're not so different from bats and we could all learn to echolocate if we practiced a bit more. It's a mistake to say that we are completely unlike bats. I don't know exactly what it's like to be a bat but I don't know exactly what it's like to be you either.