Please hit the ❤️ “Like” button at the top or bottom of this article if you enjoy it. It helps others find it.

When I made the transition from philosophy to cognitive neuroscience, I was self-conscious about my background. I was applying to serious PhD programs in a topic I didn't actually have a degree in. I hadn't taken a single course in neuroscience.

And so, as a philosophy Master's student, I reached out to people in the psychology department for some guidance. What was interesting about these conversations was how they saw philosophy. One of them told me he thought a neuroscience program might see my philosophy background as an asset since it made me "someone who knows what words mean".

He wasn't talking about knowing the weird latin phrases philosophers love to use that sound like Harry Potter spells (*Waves magic wand*—reductio ad absurdum). He saw philosophy as studying what we meant by words—investigating the concepts we use to understand the world, rather than the nature of the world.

Other professors gave me a similar vibe, that they had a somewhat deflationary view of what philosophy was about. It wasn't about answering the big questions, at least not directly. It was about taking our current thinking and clarifying it.

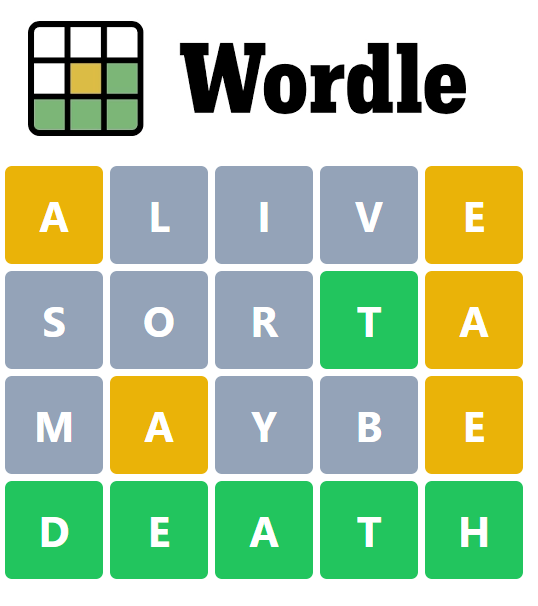

Word Play and Death

To try to illustrate this deflationary view, let me take an annoying example I've seen played out in undergraduate philosophy classes (and an annoying dinner party I attended). What is death?

We have the term "clinical death", for when the heartbeat and respiration stop. Some clinicians seem to find the term useful, presumably because 1) it's a stage people transition through before becoming "biologically dead", 2) it's a condition that calls for specific interventions (e.g. CPR), and 3) it's cool to tell people they were clinically dead for a bit.

But, astute undergrad 1 says, clinical death is reversible, so does it really qualify as "death"? My intuition is tingling and telling me dead means dead dead, like, no coming back. So this can't be death! Maybe we should put this concept of irreversibility into the definition!

But, astute undergrad 2 says, the trouble with reversibility as part of our definition is that reversibility is context dependent. We could imagine future technology that allows us to bring people back from much further along—perhaps a super-futuristic scanner that can use nanomachines to reconstruct every cell based on a scan of a body, and bring people back that we currently would comfortably have been calling dead for seconds, minutes, or even weeks or months. What if we discovered this technology after someone entered this now-reversible state? Were they dead, but then the mere discovery of the technology made them not-dead? My intuition is tingling, telling me that if someone's dead, a scientific discovery shouldn't make them suddenly not-dead!

Astute undergrad 3 pipes up: Maybe someone is only dead if it is irreversible by any technology.

Astute undergrad 4 replies: But now we need to know all possible medical technologies that will be developed in the future before we can say if someone is dead, and that seems like a dilly of a pickle.

Round and round we can go, thinking up new definitions that lead to new counter-examples, until we get stuck with different definitions that different people's intuitions tell them different things about. This is fun for a little while, and the first time encountering this conversation can force you to think more deeply about what we mean by death. But at some point it's worth asking: what are we doing here? Are we just playing a weird word game with the word death?

Notice how quickly the above came untethered from the real world. Hypothetical technology comes into play and we get into weird science fiction thought experiments.

As soon as we tie things back to the real world, it becomes easier. Why do we need a definition of death? Well, for one thing, there's legal stuff at stake. When does the last will and testament go into effect, when can we treat the body as a thing not a person, that sort of stuff. That use case would give us some reasonable constraints—like it needs to be something we can determine relatively precisely and easily, and not lead to many cases where the person gets up and starts arguing that they are still a legal person.

But now we immediately need to look at the actual, practical cases. We need to talk to doctors to get an idea of when they make determinations of when someone is irreversibly dead given our current actual medical technology, learn about legal situations in which previous tried definitions failed, and so on. We started with something that felt like philosophy, talking about a big topic (what could be bigger than life and death?), and ended up needing to actually get out of our armchairs.

Isn't there more?

But wait, we're not out of the annoying philosophy undergrad death debate yet. If a student suggested just looking at the practical cases, very quickly you would get the response: This leaves something out, what death actually is!

And here we run into the distinction I'm trying to articulate. There are two views of what we're trying to do. On one view, death is a concept that carves up reality at its joints. It's a real, metaphysical event. One traditional view of death holds that it's when the soul leaves the body—we're trying to sort out when it is the soul has left, but we lack a soul-detector. Whether there's a literal soul or not, under this view, there's a real event that we're trying to pinpoint, because of course death is really really real. On this view, even if we've sorted out every possible practical problem, there's still a metaphysical question left: the One True Way™ to characterize death. There's a feeling that, given any body in any state at any time, there is always a real answer to the question "is it alive or dead?"

The deflationary, pragmatic view is that we have learned (through nature or nurture) this concept of death, which describes certain patterns in the real world. These patterns are real, but there may be fuzzy edges, because reality is messy. We can point to the bright white and dark black, but there is grey in between. Reasonable people might disagree where those edges are—we all learned these concepts on our own, after all, and not through repeated exposure of tricky cases where someone gave us the "right" answer. If we need to distinguish the grey areas for some purpose, we can come up with a robust method for that purpose—but most human purposes don't require infinite precision. Time of death doesn't matter down to the millisecond. Exceptions are like edge-cases in software—if they become a big deal, we can try to sort them out, but some systems are complex enough that we need to deal with the occasional bug.

None of the above is meant to recapitulate a professional philosophical debate about death—I don't know much about the philosophy of death, I've just been a party to unprofessional philosophical debates about death. But the above distinction, between the deflationary view and the more realist or metaphysical view, is the distinction I was sensing in the psychology professors—they had a deflationary view, not necessarily about death, but about a wide range of philosophy.

I think this distinction tracks why I find it hard to get invested in many real philosophical debates.

Concept Play and The Ship of Theseus

The whole reason I'm writing about this is because I was reading about the Ship of Theseus and other paradoxes of "material constitution".

The Ship of Theseus is a classic thought experiment: A ship goes on a long voyage. Along the way, each plank is replaced as it gets worn out. By the time the ship returns, no single piece of the original is still in it. Further, someone else went and gathered up all of the discarded planks of the original, and rebuilt it. Now we have two ships! Which is the true "Ship of Theseus"?

There are various other classic conundrums of "material constitution" that we can think up that all make a mess of our everyday notions of when something is the same object. I love these things because they make you think more deeply about a concept, "identity", that seems so obvious and simple.

But like the undergrad death debate, it forces us to confront the fuzziness of a concept and then gets bogged down in trying to find the perfect answer. Philosophers have various stances on how to deal with the conundrums of material constitution—positing that objects can be "coincident", meaning two objects can be in the same place at the same time. Or that objects are actually 4-dimensional, with time-based properties. And so on.

All of these views have something going for them, and all have features at least some people find counterintuitive. But I find it hard to feel like I'm learning anything from reading the different proposed solutions.

We have the story of the Ship of Theseus—there's no magic going on. We know where both ships came from. We can decide to think of the two ships, prior to the one being reconstructed, as being "coincident". Sure, that's one way to think about it. But some people don't like that way of thinking about it because it's weird to think of two things in one place at a time. Maybe there's some elegant solution that makes all these edge cases seem intuitive to everyone. That would simplify things because we could just lean on that description for any possible use case (e.g. the legal battles over who owns the Ship of Theseus).

But I find these theories hard to get that excited about. Once I'm over my initial shock that my concept of identity has weird edge cases, the rest feels like some weird theoretical psychology completely isolated from the rest of cognitive science.

Concepts and Intuitions

The distinction I'm trying to draw between deflationary, pragmatic views and the metaphysical view is whether we're talking about facts about the mind or facts about the external world.

To me, and I suspect to the psychology professors I mentioned above, the bread and butter of much of philosophy—concepts and intuitions—are parts of our psychology. Our concepts come from somewhere, but not some Platonic realm. They're learned, either being built in through evolution or learned from experience. Intuition is just a label for something like our unconscious judgments of plausibility based on our tacit conceptions.

In a previous post, I talked about the philosopher Unger's criticism of analytical philosophy: much of it is arguing over "empty ideas". Either they're conceptual distinctions that can't possibly matter in the real world, or distinctions that are just so fantastical they're unlikely to come up in the real world.

If you see philosophy as about figuring out the fundamental nature of the external world, even if these ideas make no difference, you might think they are important because there's a correct answer. If, on the other hand, you think these debates are about psychological constructs, beyond a certain point the debates become boring and detached. The debates are stretching our concepts beyond their domain of applicability, and then trying to sort out how to apply them. The distinctions only matter if we can point to a case where they actually matter, but then we're not in our armchairs anymore.

All of this is to try to explain why certain philosophical questions feel inert to me—and presumably the psychology professors I mentioned in the intro, and philosophers like Unger. Maybe I just haven't heard the right motivation for these debates—maybe I missed a crucial lesson during my admittedly brief time in philosophy. But it feels like once our concepts are deflated to psychological pattern matching instead of Platonic forms, the gas goes out of a lot of these debates.

Not to say it isn't useful to think deeply about our concepts. Sometimes we'll realize those concepts are confused, and by clarifying them, we can improve our understanding of the world. Einstein credits philosophy with his breakthroughs in physics. The careful conceptual thinking of people like Mach and Poincaré about time, acceleration, and gravity led to our greatest theories of physics. But once again, these were distinctions that mattered—there were real-world, observable predictions these concepts made.

There are a few common attitudes towards philosophy: those that brush it off as meaningless wordplay, obsessed with the modern equivalent of how many angels can dance on the head of a pin; those that think of it as a humbling activity rather than a search for truth, appreciating the journey while acknowledging the lack of solutions; and those that see philosophy as truly productive, helping to solve real problems. I think there's some truth to all of these views. Many philosophical problems don't have a solution, but they're worth considering because they force us to see behind our naive folk theories. In other areas, there really can be progress, because lots of philosophy involves seeing what problems there are in biology or cognitive science or law, and helping deal with the conceptual tangles in those fields. It just involves getting out of the armchair.

Please hit the ❤️ “Like” button below if you enjoyed this post, it helps others find this article.

If you’re a Substack writer and have been enjoying Cognitive Wonderland, consider adding it to your recommendations. I really appreciate the support.

I’m currently studying as a philosophy undergrad and I sympathise with some of this. But I like to chalk it up a little differently.

I tend to lean more towards the realist side of things in general, but I think when it comes to whether philosophy matters in different ways, I think there are a few things to say.

I think many aspects of philosophy are simply attempts to understand reality, and in such a way that is the least offensive to our intuitions-understood as intellectual presentations rather than a gut feeling.

But some of the time I can find myself not really caring for some answers to philosophical questions. I think there is one true theory of time, but unless it has implications that matter (which seems entrenched in philosophical investigation) then I remain cold to possible theories. I’d rather do something else tbh!

But this strikes me as the same problem almost everything else faces. I don’t care much for professional sport, so I don’t involve myself with it. But it would be a bit of overreaching on my part if I were to conclude that professional sport was useless or a waste of time. (Though of course, you’re not arguing for this sort of conclusion for philosophy. But I do think it’s important to keep in mind.)

Another possible answer is that there are normative truths “out there” and it’s important to understand what they are so we can coincide with the reasons that apply to us. Case in point, things like objective epistemic and moral facts.

But I think one of the reasons why I champion philosophy over all the other areas of inquiry is that it’s the foundation for everything-all other areas of inquiry. And that’s pretty awesome.

In the end, I also just enjoy possessing a mind capable of having clarity. And I feel my study of philosophy has really helped me to achieve this state of affairs. Though I will say that you don’t have to study at an institution to reach this. Just engaging with philosophy on your own can do this-especially in the writing of your own philosophical ideas and arguments. I feel philosophy is especially equipped for this use provided that it’s the discipline that is built upon the making of arguments and the exploration of complex ideas in tandem.

Thank you for reading my impromptu essay. I hope I get a passing grade 🤞

I like your example of a debate about the meaning of death, as it well illustrates the slippery slope leading from a discussion of a particular topic to the twin notions that what ultimately matters is having a precise definition of the name we give to the phenomenon under discussion, and that the way to reach that definition is to box it in with increasingly tight corner cases. Lurking beneath the surface, I suspect, is a yearning for an ideal language allowing only the expression of error-free concepts.

In a nutshell, I get the impression that analytic philosophers expect that refining definitions will yield knowledge, while pragmatists expect that refining knowledge will yield definitions.