Meta-knowledge and Meta-ignorance

The Illusion of Explanatory Depth and the Curse of Knowledge

Please hit the ❤️ “Like” button if you enjoy this post, it helps others find this article.

Do you know what a penny looks like? Assuming you live in a country with pennies (or one that had them up until recently—sorry for your loss, Canada), you likely do.

Or at least, you sort of do.

If someone were to hand you a penny and a nickel, you could easily tell them apart. But if I asked you to draw the features of a penny, would you be able to remember all of the different features and put them in the right place?

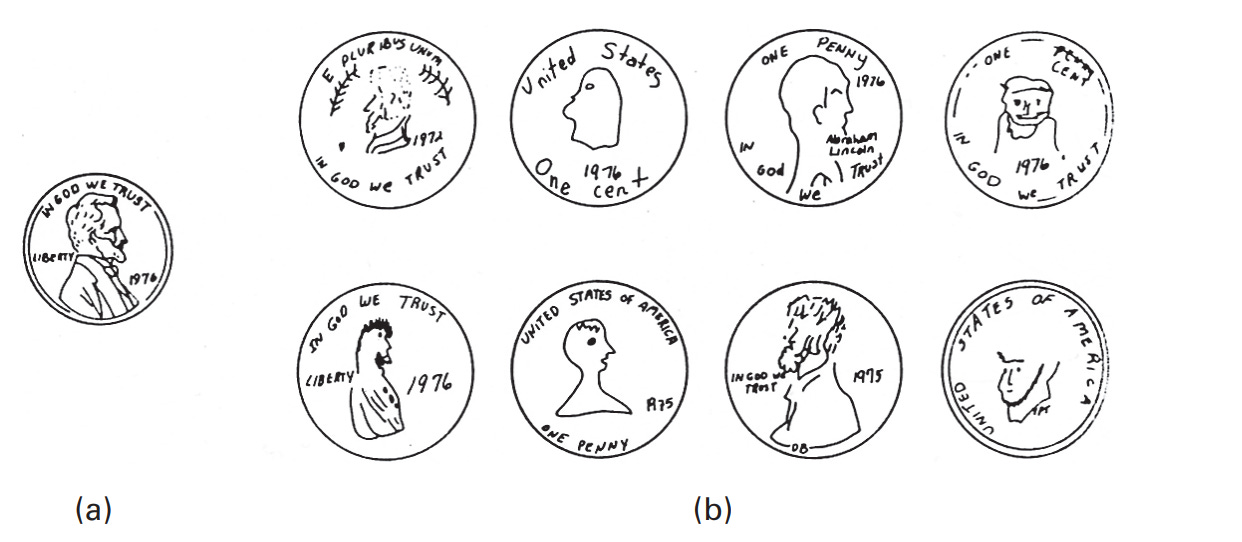

In a classic study, (American) participants were asked to do just that: draw an US penny. This was back in 1979, so people were actually still regularly handling pennies.

People weren't great at it.

I'm not referring just to the drawing skills (though, uh, yeah). Generally people missed some features like the words "In God We Trust", or put them in the wrong place, or drew old Abe Lincoln looking in the wrong direction.

It's not just reproducing the look of the coin people were bad at—when given sketches with different mistakes, only about half said the correct one was correct, and people had trouble determining the error in the others.

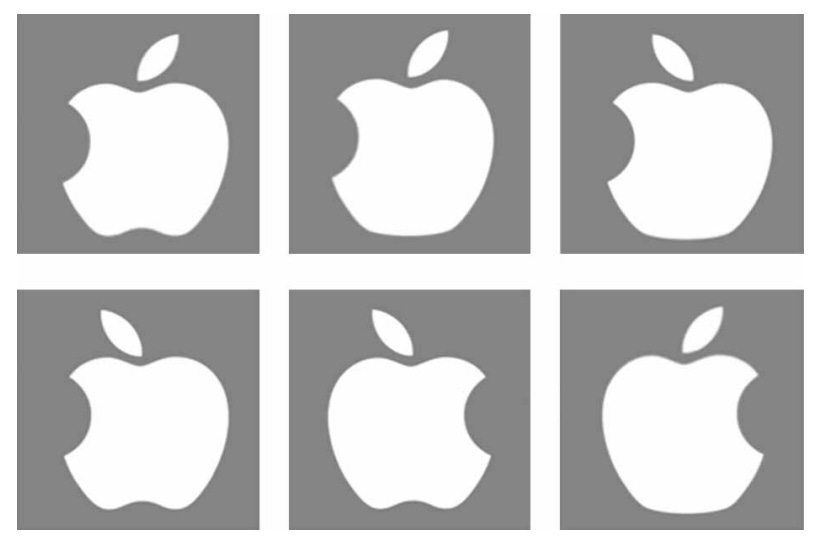

These results aren't specific to coins. Studies have shown people aren't great at knowing where a fire extinguisher in their workplace is, even if they pass it every day. Even with marketing logos designed to be recognized and iconic, we're pretty bad at telling when something is the real logo—for example, which of these is the real Apple logo?

The right answer? None of them. The bottom right one is close, but is missing the crucial apple butt indent.

This all might sound unsurprising—of course no one knows the exact details of a penny or the exact location of different objects in their environment. Why would they? They don't need that information! That sentiment is exactly right—we don't passively absorb just any information we come across, even if we come across it extremely often.

What I find more interesting, though, is our own ignorance about our ignorance. Our meta-ignorance, if you will.

The Illusion of Explanatory Depth

I've written before about how people are seemingly unaware of their own ignorance about the workings of everyday objects, like bicycles. If you ask people to draw a picture of a bicycle from memory, they do something similar to the pictures of pennies above—they can't remember where the different parts go. In the case of a bicycle, though, the parts need to be hooked up in a specific way for the bicycle to function. This isn't just a failing of remembering specific parts—it's a failing of understanding the basics of how a bicycle works.

Studies have shown that people suffer from overconfidence in their understanding of a wide range of topics: mechanical devices, natural phenomena (like how the tides work), and geographical facts. People will give themselves a high rating on how well they understand concepts from these topics, until they're asked to explain them. Then suddenly the ratings drop. This phenomenon shows up in experts as well—experts don't seem to realize how much stuff they've forgotten.

Researchers call this the Illusion of Explanatory Depth. We feel like we have a deep understanding of various things, but research shows we're surprised by the limitations of our understanding.

Our knowledge about our knowledge—our meta-knowledge—is far from perfect.

Unknown Knowns

On February 12, 2002, during news briefing about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, the United States Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfield gave this statement on meta-knowledge:

[T]here are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don't know we don't know.

—Donald Rumsfield

The illusion of explanatory depth shows us a particular type of unknown unknown—something that we don't realize we don't know, simply because we think we know them.

Lovers of Boolean logic will realize there is a strange omission in Rumsfield's statement. We have known-knowns, known-unknowns, and unknown-unknowns, but no unknown-knowns! There's probably a geopolitical joke in here somewhere.

Unknown-knowns are a thing! In one experiment, participants were asked to tap out the tune to a popular song. The tappers, listening to their own tapping, thought listeners would be able to name about 50% of songs. But listeners' accuracy was actually only 2.5%. The tappers were oblivious to the fact that the song sounded obvious to them because they were unconsciously filling in the pitch of the notes.

It's embarrassing to realize I've done the same thing—happily tapped out a song, expecting my wife to know I was tapping out Jingle Bells, only to be met with a questioning raised eyebrow. Try it sometime, it's wild how obvious it will seem to the tapper what the song is and how frustratingly underspecified it seems to the listener.

We have all kinds of knowledge that unconsciously shapes our experiences.

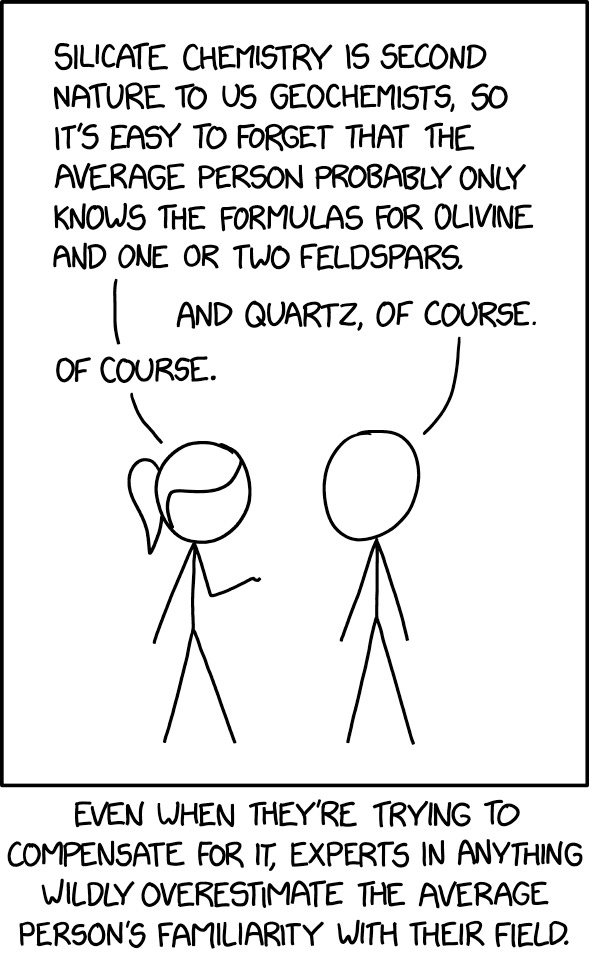

It's a common observation that experts aren't necessarily the best teachers. Having a skill doesn't necessarily equip you to recognize what knowledge someone else lacks, and can make you oblivious to the depth of your own knowledge—sometimes called the curse of knowledge. Research backs this up—experts in math are bad at understanding what skills less experienced students need to solve math problems. We tend to take our own knowledge for granted.

In grad school, when we had a new crop of students join the lab, I remember being surprised by the hundred different little incidents of realizing the new students didn't have some knowledge that I didn't even realize I had. Statistics, brain anatomy, cognitive psychology—little bits of knowledge I wouldn't be able to call to mind to name as things I had learned, until I was around people who were starting to learn those things themselves.

We're used to calling out the overconfidence of people, like political commentators who make bold predictions and then move onto the next bold prediction when the previous one fails to materialize, never acknowledging their poor track record. But lack of metaknowledge cuts both ways. "I know that I know nothing" is a sentiment often misattributed to Socrates, and sometimes taken to be a statement of great humility and self-knowledge. But the statement makes the mistake of metaknowledge in the opposite direction—we are often unaware of the depth of our own knowledge.

Our minds are full of gaps we don’t notice. There are things we don't realize we don't know, but also things we don't realize we do know. Knowing something isn't the same as knowing we know it. To misquote Socrates again, knowing thyself (or at least, our state of knowledge) is hard.

Please hit the ❤️ “Like” button below if you enjoyed this post, it helps others find this article.

If you’re a Substack writer and have been enjoying Cognitive Wonderland, consider adding it to your recommendations. I really appreciate the support.

My kid is constantly irritated w my husband and me for not knowing how things work. “You use xyz every day of your life and you never thought to ASK??!!!”

Hmmm, is the tapping example an “unknown known?” I would think of an unknown known as something more like:

1) A person thinks they won’t know how to do something, but then once they start doing it they realize they actually *do* know how.

2) You think you don’t know some factual statement, but then a couple seconds later you remember and realize you actually do know.

The tapping example is different. The noun “known” refers to one person, but the adjective “unknown” is a *different* person. Contrast this with the other three in the set: the adjective and the noun refer to the same group (collective society.)