The Cognitive Mechanics of Creativity

What creativity is, how we do it, and how expertise plays a role in it

Please hit the ❤️ “Like” button if you enjoy this post, it helps others find this article.

A little while ago, I was invited by

to attend and give a talk at a small digital conference he was putting together on Thinkies. Thinkies are strategies for creative problem solving that Kent has thought up while working in the software world.Kent wanted to have a "fireside chat" with me about the cognitive science of creativity. What is creativity? What are we doing when we think creatively? That sort of stuff.

I figured since I did some research and made notes in preparation for that, I might as well write a post about it.

What is creativity?

Originality on its own isn't creativity. Here's a totally original sequence of letters: "dfoigjmeo" (created by smashing my hands on my keyboard, verified as original by the foolproof method of googling). It's obviously not creative. Similarly, something that's effective but not original is not creative—using a hammer to drive a nail through a board is very effective, but if you saw someone doing that you wouldn't think "Wow, what a creative solution." It's too common, it isn't original.

But when something is both original and effective, it's creative. If someone needed to drive a nail through a board, but didn't have a hammer, they might need to come up with a creative solution. Maybe they have a brick laying around—they realize that can be used to "hammer" the nail. It's a minor creative solution—it's original (they may not have ever seen someone hammering a nail with a brick before), and presumably effective.

Of course, "effective" needs to be defined pretty broadly to capture everything we think of as creative. In art, "effectiveness" can't be captured by how well a concrete problem is solved. But art that we recognize as creative does something—maybe convey an emotion, or draw and hold interest.

Now, this definition isn't perfect, and some researchers certainly show a level of discomfort with it. But it's a good working definition with a long history, so it's a useful framework to keep in mind as we dig further into creativity and idea generation.

How do we come up with something creative?

Creativity researchers usually talk about two types of thinking essential for coming up with creative ideas: divergent thinking and convergent thinking. Divergent thinking is the ability to come up with lots of different ideas to a problem. Convergent thinking is evaluating and filtering ideas—taking a bunch of the raw ideas generated and figuring out which ones are worth pursuing.

Many models of creative thinking suggest there's a sort of Darwinian process of iteratively generating ideas through divergent thinking, selecting through convergent thinking, then diverging again using the surviving ideas as fodder for the next generation.

Divergent thought is more often the focus of creativity research—it's not hard to imagine how we might evaluate ideas once we have them, but how do we come up with ideas to begin with?

Ideas don't just pop into existence from nowhere. We have an enormous amount of conceptual knowledge we can draw on to generate new ideas. Two types of processes that cognitive scientists talk about in the context of idea generation are conceptual combination and abstraction.

Conceptual combination is simply taking two ideas that aren't usually associated and putting them together. Think of just about any bad pitch you've heard for a science fiction movie—it's usually "normal thing" + "IN SPACE". TV Tropes calls this "recycled in space", where the idea of one movie is recycled with some simple twist (like "in space") is added. For example, Dracula 3000 is Dracula… IN SPACE. Jason X is Friday the 13th… IN SPACE. As a less literal and cross-franchise example, according to TV Tropes, Alien was originally pitched as Jaws… IN SPACE.

These are all silly examples of doing the most obvious combination of concepts. But exactly how you combine them is a whole other task—which features of Jaws do you use for Alien? They didn't put a literal shark in space, the analogy is more abstract: "Big scary thing might eat you but you can't easily find it". Similarly, there's no beach or beach-goers, but folks on a spaceship. The conceptual linkage used relies on a bunch of abstractions and analogies rather than a straightforward smashing together of two (or more) concepts.

And that brings us to another key component of idea generation, abstraction: finding which properties of a particular concept to retain and which ones to abstract away when solving a problem or trying to come up with an idea. Going back to the "using a brick as a hammer" example above, it involves an abstraction: abstracting the key feature of hammers (their hardness) and using that to look for other possible tools with that same feature.

So when thinking up new creative ideas, we abstract away properties of some concepts, borrow properties from other concepts, and sometimes stretch or transform properties of concepts, to come up with something new.

Creative Problem Solving

The above is all well and good for generating ideas in an open-ended context. But what about creative problem solving, where there's a concrete problem and a solution with defined criteria is needed?

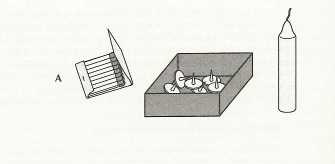

The candle problem is a classic example of creative problem solving. Psychologists put participants in a room and instructed them to find a way to affix a candle to a cork board on the wall. Here's what they were given to complete their task:

What would you do? Most people try to figure out how to get the tacks to hold up the candle, or melt the wax of the candle to use it as an adhesive. These solutions don't work.

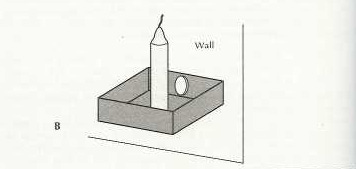

The real solution? Empty out the box, use the tacks to hold up the box, and use the box as a platform to hold the candle:

Not many people find this solution. However, if the task is changed slightly, so that the thumbtacks are piled outside of the box, rather than inside, people tend to find the solution. I suspect this is for two reasons: 1) in the original, the box is seen as incidental—just something to hold the tacks, not part of the potential solution. 2) As pointed out in Hofstadter and Sander's book, Surfaces and Essences, finding the solution requires two leaps of abstraction: From "thumbtack box" to "box", and from "box" to "stand". When the tacks are outside the box, it only requires one leap of abstraction: "box" to "stand".

What are we to make of this? I think some of the features we see as creative problem solving are similar to how we generate any other creative idea: it often involves abstraction to find connections that allow us to see atypical possibilities.

What makes someone creative?

It's common to think that some people are just more creative than others. But creativity isn't a single ability, it involves many different processes, and they differ from one domain to another. A brilliant water colorer isn't going to be amazing at coming up with creative solutions to software engineering problems.

But there are certain features that are associated with creativity. Some of these are pretty straightforward and intuitive: as a personality trait, being open to experience is associated with more creativity, and it's been suggested that being in an environment that is tolerant of exploring new things can foster creativity.

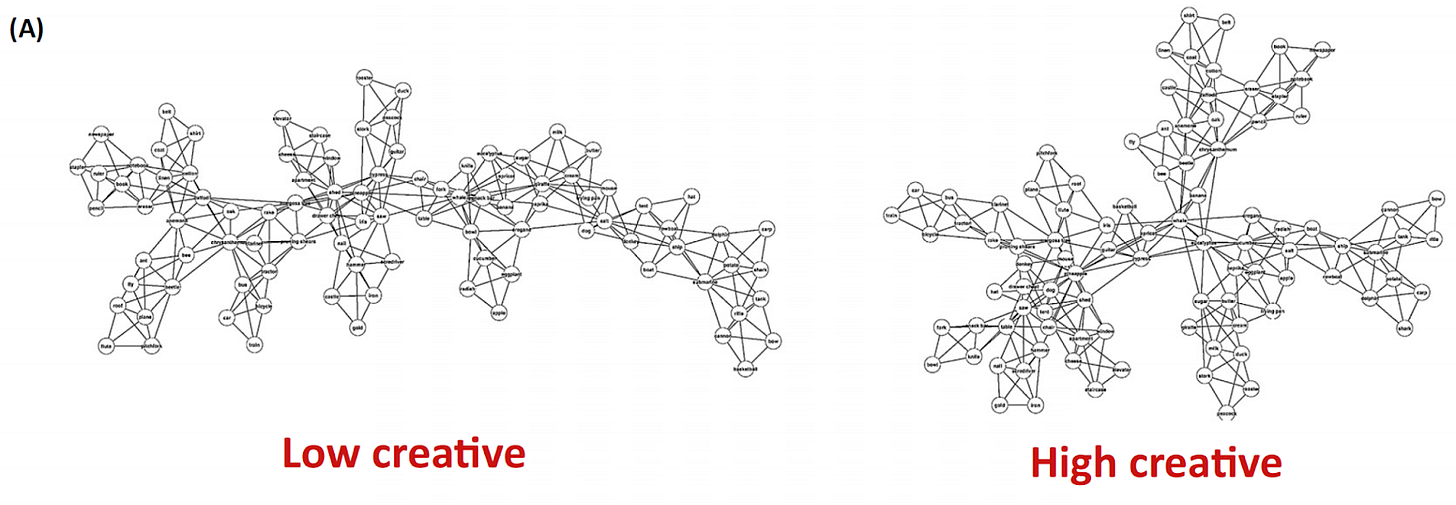

A much more interesting finding is that highly creative people seem to have more connections in their semantic memory than less creative people. You can think of semantic memory as our store of concepts—everything from "staircase" to "justice". In more creative individuals, the web of associations between these concepts tends to be denser—there are more connections than in the semantic memories of less creative individuals. That means that when they try to generate new ideas, it takes fewer leaps to find surprising yet meaningful connections between seemingly unrelated ideas.

The idea is that it's easier for highly creative folks to find disparate connections between concepts because they don't have to search around their semantic webs as much—making it easier to make remote connections between concepts.

The concepts involved in a creative project are often domain-specific, and research has shown knowledge of a domain is a prerequisite to creativity. Having a rich semantic web to draw on for a given domain is going to help you find connections within the relevant domain. You also need to have the expertise to judge what's useful for a problem in a specific domain, so you're not just generating novel but useless ideas. It's a common observation that people highly skilled in a creative domain often have good intuition—experienced storytellers, artists, and musicians are often able to quickly assess when an idea just won't work (at least, better than those of us working in a creative domain without much skill). Creative people need to be able to generate a lot of ideas but also be able to filter down to the useful ones, and that requires expertise in the domain.

Closing thoughts

This is only a rough sketch of some features of creativity. There's still a lot we don't understand, and much of what we do know comes from simplified tasks and artificial settings. But still, it provides a more grounded image of creativity: it isn’t a single, magical trait. It's a complicated mix of different cognitive skills and networks of knowledge.

Creativity means different things in different contexts. In poetry, it might mean seeing an unexpected connection between ideas to create a fitting but surprising metaphor. In software engineering, it might mean seeing the right abstractions to modularize your code. In both cases, what we call “creative insight” depends not only on the ability to generate novel ideas, but also on knowing what counts as a good idea in a given domain. Being able to judge an idea, see the right abstractions, and find surprising connections all depend on expertise in the domain.

People sometimes talk about creativity as if it's some mystical spark that makes ideas appear from nowhere to a lucky few. When we treat creativity as a monolith—something you either have or don’t—we overlook how much of it depends on your environment and your conceptual knowledge. Deepening expertise helps us deepen our conceptual structures and see more novel connections in a given domain.

Just think about all of the expertise required to come up with Space Sharks. They had to know about space and sharks. Now that's creativity.

Please hit the ❤️ “Like” button below if you enjoyed this post, it helps others find this article.

If you’re a Substack writer and have been enjoying Cognitive Wonderland, consider adding it to your recommendations. I really appreciate the support.

Great, creative piece. Thank you.

Interesting article. this bit: "The concepts involved in a creative project are often domain-specific, and research has shown knowledge of a domain is a prerequisite to creativity."

Western people often criticize the way of teaching art in China , claiming it is "not creative", yet the Chinese perspective is to teach the tools first. Teach the way great artists painted to become familiar with the tools (calligraphy brush, ink etc) and then find your own style. In other words, know your domain and be creative once you know your domain. That style certainly fits that sentence above.