Theism, Dualism, and Webs of Belief

The complexity of minds, the feats of dumb matter, God, and souls

I was raised Roman Catholic. Now I’m an atheist.

I couldn’t tell you when I initially lost faith. Sometime as a teenager I started having questions about the whole religion thing. By the time I reached college, I was an atheist. During my undergraduate years, I was obsessed with religion. I read Christian apologetics books (I still have many on my bookshelf), read books about the history and anthropology of religion, watched debates and lectures on the existence of God. I took a philosophy of religion class and sought believers to talk to, even attending Bible studies and Christian clubs. My turn from belief in God was a sort of “coming of age” intellectually, so it kept drawing me back. My atheism was a big part of my worldview that came from me and an explicit rejection of what authority figures had taught me my entire life. I had to understand why others believed. I had to make sure I was right.

These days, I find it hard to muster that same excitement about the question of God.

This is partially because it’s well-charted territory for me now. I’ve heard the arguments plenty of times. But it’s also about the arguments themselves—they often feel almost performative. It’s like the two sides are just talking past each other. Theists make their arguments—the universe needed something to start it, the universe needed something to fine tune it, etc. Atheists counter that these arguments are “God of the gaps” arguments—we don’t know how something happened, therefore it’s evidence of God. This feels more like a dismissal than an engagement for the theist, who believes God is the best explanation for these observations. Atheists point to the existence of unnecessary suffering in the universe, and theists have various ways of explaining why God would allow that. Atheists sometimes make vague claims that science disproves religion, but it’s hard to point to a particular scientific claim that overturns any possible belief in a deity. There’s very little convincing each other.

This post is my attempt to articulate why religious debate doesn’t connect, at least from my perspective. Of course, it will end up implicitly being an argument for my view: atheism. So maybe this is just my sneaky way of revisiting the interests of my youth while pretending to be above it.

Theism and Dualism

In Coherence in Thought and Action, Paul Thagard argues that debates should look at theism (belief in God) and dualism (belief in immaterial souls) as not separate issues, but mutually supporting ones to consider together.

The overall thesis of Thagard’s book is about a formal framework for epistemic coherence. Coherence is a philosophical view of what makes beliefs justified based on how they interact with other beliefs—how much they explain, how well supported they are by observations, and how well they fit with other things we take to be true. Many true beliefs are going to have observations that are in conflict. I believe gravity pulls things to Earth, but see birds fly all the time. I need additional explanations to explain those conflicts—birds can generate lift with their wings pushing against air.

Instead of thinking of the arguments for or against God as logical proofs, they’re instead attempts to gesture at aspects of the world that cohere better with one theory or the other. Each worldview is a web of beliefs. They will have different observations they can naturally explain—for example, theism has natural explanations for how the universe started and appears fine-tuned (God did it), while an atheistic worldview has a more natural explanation for why there’s unnecessary suffering in the world (you would expect bad stuff to happen in an ungoverned natural world). These map onto the arguments for or against God. The point isn’t that the other worldview can’t explain these, but that it requires them to add additional explanations to do so. You have to look at the overall picture to decide which worldview is more coherent. Any individual argument won’t solve it.

Thagard’s point that dualism and theism are bound up together rings true to me. These are very mutually reinforcing belief systems. For one thing, if souls exist, it would be hard to make sense of where they came from without invoking a god. It’s not clear how evolution could have created souls. But more importantly, the existence of God is a lot more plausible if you believe in souls. God, after all, is sort of a mega-soul. If souls exist in your worldview, it isn’t that big a leap to say there’s a really big one out there. And we know what kinds of stuff souls/minds can do: they are good at designing and causing stuff, exactly the things God is usually used to explain about the universe. It all “hangs together” well.

If you believe in souls, “God of the gaps” isn’t the logical fallacy it’s often laid out as. It’s an inference to the best explanation, but there’s an explanation available to you that's not available to non-dualists: an immaterial mind.

Spontaneous Generation and Vitalism

For millennia (from at least Aristotle until the mid-19th century), spontaneous generation was a well-regarded theory. It held that life regularly popped into existence from dead matter. Under this theory, maggots and mold spontaneously formed on decaying matter. This seemed plausible because, as anyone in charge of the garbage can attest to, maggots seem to appear out of nowhere. Fungus just starts growing on stuff for seemingly no reason (the spores aren’t easily visible). Historically some people believed things like clams, frogs, and mice spontaneously generate too—once you accept it for some life, it seems plausible it applies to others, and mice certainly seem to just “appear” sometimes.

Nowadays, we recognize this idea as obviously wrong. Life like maggots, fungus, even bacteria, are complex. Their genetic code has enormous amounts of very specific information. That all that the specific DNA for those creatures could reliably pop into existence regularly is laughably naïve, based on our modern understanding of the biochemistry of life.

So why did people believe in spontaneous generation for so long? For one thing, we didn't know how life worked. It seemed obviously very different from dumb, dead matter. Life moved on its own, had goals like seeking food, it seemed to have something that dead matter like rocks lacked. Life seemed like a fundamentally different thing from everything else in the world.

Vitalism was the view that there's a “vital force” or different physical laws governing living things that makes them different from non-living matter. Aristotle thought the air was filled with vital heat that interacted with water to create a "froth" that became life. John Needham, an 18th century English biologist, believed in a "vegetative force" that brought special living molecules together to form life.

For the vitalists, life seemed obviously different from non-life and it wasn't a big leap from there to posit that there was something fundamentally different about it. The observations of life seeming to pop out of nowhere then become easy to explain: this special life stuff must be coming together in the right ways. If you don't know how enormously complex the underlying machinery is and think there's just one special ingredient for life, it's easier to see how it could come together easily.

The picture I'm trying to paint here is that these beliefs (vitalism and spontaneous generation) were both totally reasonable based on what was known at the time. Underpinning both of them was a lack of understanding just how complex the mechanisms of life are.

Now that we know more about biochemistry, we know how incredibly complex the machinery of cells is. We know how much information DNA holds, and the machinery that goes into taking that information and forming proteins to carry out different actions in the cell. These different proteins interact with molecules in the environment to create complex behavior.

The humble E. coli contains proteins that form simple appendages (flagella) for moving around, and proteins that form receptors for the sugars they consume. When the receptors detect sugar, they modulate the activity of the flagella, causing the E. coli to move towards the sugar source. This is incredibly cool, goal-directed behavior. And we understand how it comes about through the interactions of molecules.

Dead molecules, put together in a complex way, produce the complex and seemingly inexplicable behavior we see in life (for a richer picture of how physical mechanisms can give rise to goal-directed behavior, the first half of Free Agents is an awesome summary—don't take this as an endorsement of Mitchell's views on free will. I'm a staunch compatibilist… but that's a story for another post).

Before our modern understanding of biology, it was hard to see how life could be built out of the same stuff as everything else. Positing a different kind of stuff made sense. Once we understood how biochemical mechanisms can give rise to those hard to explain aspects of life, a door opened. We can dig further and understand life using the same concepts that explain the physical makeup of our world. There's no need for vegetative forces—and carefully controlled experiments showed spontaneous generation does not occur.

Back to Dualism and Theism

The analogy I want to draw is: vitalism is to spontaneous generation as dualism is to theism. It's not a perfect analogy (there are various forms of vitalism that work less well for this), but I think it's pretty apt.

Minds are so complex it's difficult to imagine how they could be built out of "dead" matter, just like life prior to our understanding of biochemistry. We can try to explain the complexity of minds by appealing to them being made of different stuff (souls) just like we can “explain” the complexity of life with vital forces. And just like vitalism allowed the explanation of seeming spontaneous generation, souls let you explain other things: we know minds are capable of intelligence and causing things, so suddenly we can answer the big "why" questions about the universe with another soul: God.

Again, I think this is a reasonable and coherent picture of the world. Vitalism and spontaneous generation hang together well because they support each other. Once you accept one, the other feels more plausible. Similarly, if you believe in souls, that minds are made of some immaterial other stuff, it really doesn't take an enormous leap to believe in God.

But, like vitalism, I think dualism is built on an underestimation of what "dead" matter is capable of. Vitalism relies on a simplified view of life, and dualism relies on a simplified view of the mind.

Dualism versus the Amazing Power of Dead Matter

It won't come as a big shocker that I'm not a dualist. At this point it's only natural that I offer some arguments against dualism.

There's the classic problem of mind-body interaction. Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia took Descartes to task for this problem in their correspondence. Descartes is the philosopher most commonly associated with the dualist position, but for all his fame and brilliance, he wasn’t ever able to give Princess Elisabeth a satisfying response. The basic problem is this: If souls are a different "thing" than physical matter, how do they interact with physical matter? If our souls impact our actions, they must. To move your arm, your soul would need to have a way to interact with the motor processing parts of your brain to cause the nerve impulse that projects down your arm to activate the muscles. The immaterial soul affecting the material brain would be an odd type of causation (and call into question what it means to say the soul is immaterial). More significantly, it would violate the laws of physics if sometimes some immaterial thing prods our neurons. If an immaterial soul can change the electrical activity in your brain, it's unclear how it would do so and not violate physical laws like conservation of energy.

Second, we know physical alterations of the brain impact the mind. Most of us have experienced how psychopharmaceuticals affect a wide range of mind functions—alcohol changes our perception, mood, judgment, and memory. It does so by crossing the blood-brain barrier and acting as a depressant on the central nervous system—physical changes to the brain. Damage to the brain can cause changes to personality, including changes to what we would consider moral behavior. Brain damage can impair decision-making. Alzheimer's disease is characterized by amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and loss of neurons in subcortical parts of the brain possibly caused by neuroinflammation. It causes a wide-range of changes to the mind, including the ability to remember, but also mood swings, loss of motivation, and other cognitive and behavioral changes.

To sum up this point: our perception, mood, personality, decision-making, conscious experiences, and ability to form and recall memories are all affected by physical changes to the brain. Functions we regularly think of as core to who we are can be changed by physically altering the brain. This is all easy to make sense of if you believe the mind is physically instantiated by the brain.

I have no doubt you could explain all of this if you believe in souls. Perhaps the brain is necessary but not sufficient for various cognitive functions. The point is just that you would have a lot of explaining to do. Using Thagard's terminology, these extra explanations reduce the coherence of the dualist viewpoint, making it a worse explanation of our world.

Finally, let me give a constructive case for physicalism (the view that the mind is made of matter) over dualism. The primary appeal of dualism is that it's so hard to imagine everything the mind does—everything that we do—as arising from physical mechanisms (note the analogy to the motivation for vitalism). The thing is, physical mechanisms can do incredible things! We shouldn't underestimate them.

We know that the mechanisms of evolution by natural selection can create design. Dumb processes have created things more complicated than any machine humans have ever built: multicellular life. Every lifeform we see has an amazing amount of information encoded in their DNA. All of that information was built up by a process of random variation combined with selection pressures. Dumb but understandable mechanisms create information and design.

We saw above how simple mechanisms in E. Coli, designed by evolution, can give rise to goal-directed behavior. Scientists have studied more sophisticated mechanisms in depth, giving us a rich picture of how more complex creatures like C. elegans function—we understand how their genetic code influences their nervous system, how their nervous system allows behavior and learning, how they detect and move to or away from things they like or don't like. We understand these things down to (at least in many cases) the molecular details. From fruit flies to humans, we have a range of complex behaviors we understand to various degrees—but for all of them, we have built up a rich picture of the mechanisms that allow for the complexity we see, some in finer detail than others.

The "dumb" matter of a computer can do complex mathematics; beat world champions at chess, go, and DotA 2; classify objects in pictures; and as we've seen lately, even write poetry or create pictures from descriptions. I'm not claiming computers are minds. But computers are indisputably dumb matter and can do intelligent things. It’s really surprising what they are capable of if you think about the fact computers are just refined rock and sand.

We can get design, goals, and intelligence out of dumb matter. We have a plethora of physical mechanisms we know exist to explain the workings of the mind. The link between mind function and brain function is so strong, it’s hard to explain how there could be such a strong link if the mind is some non-physical thing. With the knowledge of what "dumb" matter is capable of, it becomes harder to motivate reaching for soul-stuff to explain the mind.

Whether we’re talking about bacteria, computers, or minds, there's no magic dust that makes inert matter spring to life. There are completely comprehensible mechanisms that do. These mechanisms are complex, but they are understandable. The world is open to us to take apart and understand. There aren't souls, there's just the most complicated physical mechanism we've ever found in the universe, filled with billions of parts (each their own little complex machine) and trillions of interconnections. And it sits in each of our skulls.

Science, Religion, and Atheism

To sum up, I think a better way to think about the conflict between theism and naturalistic worldviews is to view them as two competing webs of belief. Belief in souls is a big part of the theistic web. There's nothing logically incoherent about the theistic web, but a greater understanding of how dumb matter can do smart things makes souls a less good explanation. Without souls, the idea there is some other immaterial mind (God) becomes more of a stretch. If our minds are created from enormously complex parts interacting in sophisticated ways, positing a non-material mega-mind seems like positing an enormously complex and specific mechanism to explain observations. It feels arbitrary and poorly motivated.

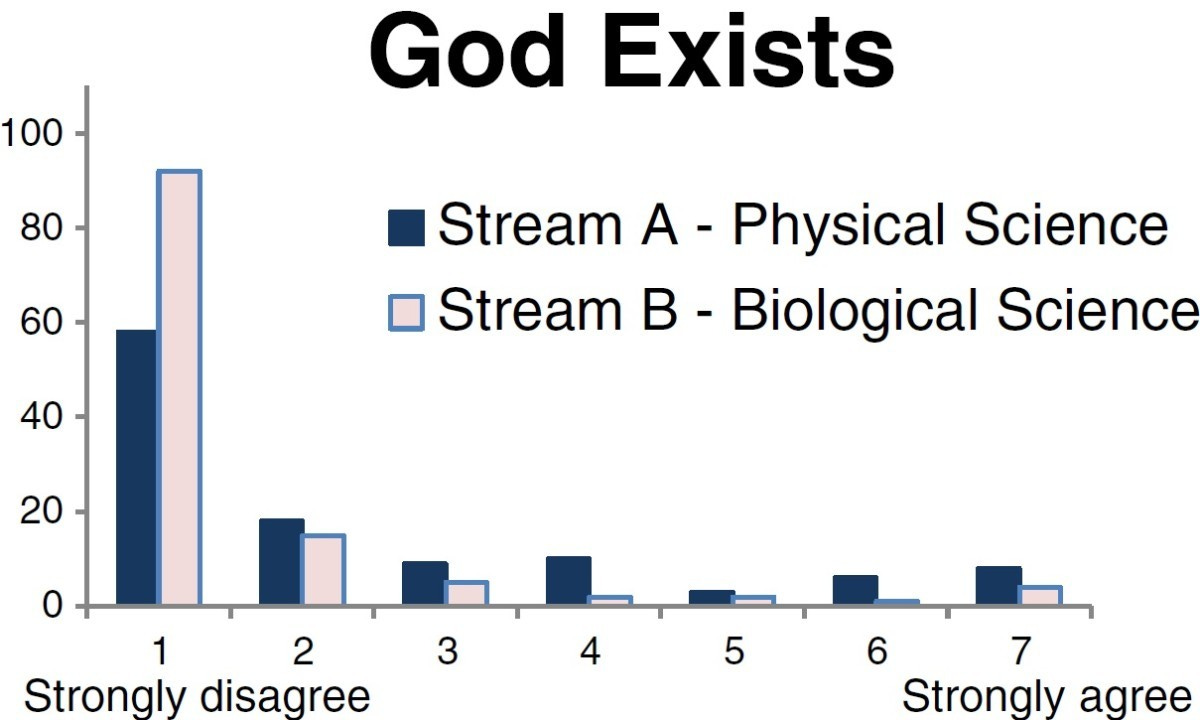

I think this explains the common conception that science is at odds with religion. It's true that scientists are significantly less likely to believe in God, and among elite scientists theistic beliefs are a rare exception. It isn't because some scientific finding disproves God, but just that greater exposure to our understanding of "dumb" matter makes you realize it might be all we need to explain the universe.

This is why I lost interest in the philosophy of religion. You can debate the arguments for or against God all you want, but at the end of the day I don't believe in God because that's a less coherent worldview based on my understanding of the wider world, especially the mind, brain, and biology. I can't simply transplant my understanding of the world onto someone else to convince them of my view, and similarly, the arguments for theism aren't of much interest to me because God itself seems like a poor explanation for anything without the supporting belief in souls. I can be at peace with other people believing, knowing they have had different experiences than me that might make theism a more coherent belief system for them, while still being confident in my own beliefs.

In his book on religion (Breaking the Spell), the late Daniel Dennett called proving or disproving God's existence "a quixotic quest". Supposed proofs change very few minds on the question of God. What's more important is to keep digging, trying to understand the world. By learning more about our world, learning the mechanisms behind the seemingly magical, we enrich our worldview in unexpected ways and refine our beliefs towards what is true.

Great post, and I agree with a lot of your reflections, and the emphasis on coherence/abduction.

But as a dualist I feel the need to criticize some of your arguments.

With regards to the interaction problem, I don't think there really is a problem there, or at least not anymore than there is a problem for the physicalist. Sure, we don't know the exact mechanism by which mental substance interacts with physical substance and vice versa, but we also don't know exactly how anything interacts with anything. If two billiard balls hit each other, you can always ask a further question of why one imparted its momentum on the other. At some point we just have to say "it just happens". It also sounds a lot less scary if you say "psychophysical laws" rather than mental substance interacting with physical substance. Just as there are laws for how physical matter interacts, there are laws for the relationship between physical and mental states.

Dualists also don't dispute that mental states have a very strong relationship to brain states. That is just obvious. But it is just not clear what the inference is from differences in physical states causing differences in mental states to mental states being physical states - there is nothing surprising about the close connection on dualism. Perhaps if you hold a very strong view where much of your personality is determined by your soul, but I don't know of many contemporary dualists who would hold to such a view - I at least wouldn't want to defend that.

As for the causal closure/conservation of energy argument, you can take two lines. One is just a non-interactionist dualism, where the soul doesn't cause any physical changes, but just supervenes on physical states. Another is just to deny conservation. After all, why should we think that conservation holds in the brain, if we have reason to think that souls can cause actions. Sure, we have observed conservation holding in many other cases, but nobody is disputing that it would hold in those cases. So pointing to cases which neither theory predicts would break causal closure is not going to provide any evidence for or against either theory.

I also think the inference from science explaining complex functional relations to science explaining consciousness is unwarranted. Sure, we can explain all sorts of structural truths in science; how such and such states relate to such and such states, and how one state causes another. But that does nothing to explain the qualitative feel of consciousness.

But again, really enjoyed your post!

Excellent post. I want to see so much more writing like this on Substack--intelligent, thought-provoking, well-written posts. And this bit: "I'm not claiming computers are minds. But computers are indisputably dumb matter and can do intelligent things. It’s really surprising what they are capable of if you think about the fact computers are just refined rock and sand." Wow. Amidst a brilliant post, for some reason, this statement really struck me!