Please hit the ❤️ “Like” button at the top or bottom of this article if you enjoy it. It helps others find it.

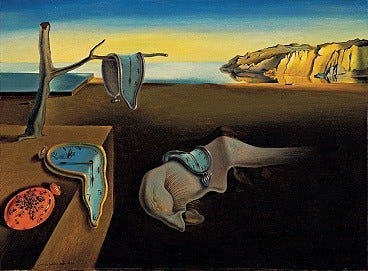

Time flies when you're having fun. The days are long but the years are short. A watched pot never boils.

Time perception is weird. If you've ever had to do public speaking, you've probably noticed a weird phenomenon: listening to someone talk for five minutes feels painfully long, but feels like nothing when you're the one talking.

This is probably why open bars are now common at weddings: you need alcohol to get through the toasts—and it increases the chances of an interesting speech.

But if you think about it, it's kind of astonishing that we can judge time as accurately as we can. Across a wide range of activities, we're able to pretty accurately distinguish 5-minutes from 20-minutes (except, apparently, public speaking). It's not like we're consciously tracking the time. We can even roughly estimate the time that we've been asleep.

But, even when we know the amount of time that's passed, we'll sometimes talk about how it passed "quickly" or "slowly". If a minute is a minute, why does it sometimes feel like more?

I got curious about all this stuff (okay, I got curious about why people ramble in public speeches and got side-tracked down this rabbit hole) so I decided to look into it.

Internal Clocks

Unlike computers, we humans don't come with a built-in clock that tracks time precisely. We do, however, have a built-in clock that tracks time imprecisely: the circadian clock. The circadian clock is a little cluster of neurons in your hypothalamus that coordinates various bodily functions that occur on a 24-hour cycle—like releasing melatonin, the hormone that signals to our body that it's sleepy time. The circadian clock receives signals directly from photosensitive cells in the retina, which allows the clock to use daylight to adjust to stay synchronized to the day-night cycle.

Contrary to some popular belief, the circadian clock is pretty darn accurate without outside information. While early studies claimed it "drifts" towards a 25 hour cycle, more recent studies estimate humans' circadian rhythm on average to be just a few minutes above 24 hours.

Despite this, there are a lot of problems with the circadian clock as an all-purpose time keeper. For one thing, it's a messy biological process that relies on complex feedback loops between proteins and gene expressions. All of the interacting parts "know" what to do when they are in a particular state, but there's no timestamp or clock hand to tell them what time it is currently. Rather than thinking of it as a literal clock, it's better to think of it as an orchestra playing a 24-hour long song—they know what comes next based on where they are now, but that doesn't mean they could tell you, down to the second, precisely where they are in the song.

But the circadian clock isn't the only rhythmic process in our bodies. We have a bunch of others that could be thought of as much shorter "ticks" of a clock—our heartbeat and breathing—which are controlled by rhythmic pulses in our brains. Early theories proposed our sense of time came from these or related biological processes.

But those processes can't be the full story because so many different factors can influence our perception of time. Not only can our physiological state affect time perception, but our mood, what we're paying attention to, how hard what we're doing is, and how old we are can all play a part.

Contemporary theories of time perception are surprisingly vague and complicated, and the research is far from definitive. But the overall picture is that our sense of time relies on attention, memory, and other mechanisms in different mixes at different intervals.

For short periods of time, those from a few seconds to a minute or two, attention seems to play a large role in our judgments of duration. When our attention is under heavy load, like when we're performing a difficult task, we tend to underestimate the time—as if our attention has "missed" ticks of an internal clock. This might be why wedding speech folks bloviate—their attention is on what they're talking about, making them underestimate how long they've been speaking for.

For amounts of time longer than a couple of minutes, theories point to long-term memory as playing a central role in our determination of how long has passed. Our short-term (or "working") memory doesn't persist much beyond a minute, so to keep track of how long something has taken beyond that point, we need to rely on other resources.

If, for short periods of time, we are accumulating "ticks" of a theoretical internal clock, for periods of minutes or longer we make a more complex inference based on multiple factors—namely, we combine memory storage of the internal clock with other aspects of memory to try to piece together the time. Factors like how many changes we've noticed in our internal states or environment are used—possibly an attempt to compensate for the bias caused by the "ticks" we miss from a strain on our attention. When there are a lot of changes, people report time has moved fast, and adjust their estimates of the amount of time down.

Passage of time

Our sense of time isn't just about our ability to objectively judge how long some event was. More interesting are our subjective perceptions of time, when it moves fast or slow. People will say things like "This week is just flying by."

When we look back over a long period of time, we're completely relying on our memories of that period. When we say it feels like the past year has flown by, it's not really clear what it is we're feeling. We might think of where things were a year ago and think about whether the time since then feels like a full year, but it's not like we can hold each moment from the past year in our head at once. Instead, we must be using some kind of heuristic.

It's pretty widely believed that time seems to speed up as we get older. People love to come up with explanations for this—like that there are fewer memorable events as you get older, or fewer surprises that change our context. If these were right, it would give us an idea of what we are doing when we judge how quickly a year has passed—we're looking at how much has happened that we haven't experienced before and comparing that to the objective amount of time.

But there are two things wrong with this. One, when researchers checked, there was no empirical support for these hypotheses. Perhaps more importantly, there isn't a difference in how quickly older and younger people report time moving in the present moment or over the past week, month, or year. Yet everyone reports that time is moving faster than it was for them before.

How do we make sense of that? The one thing that does seem to predict how quickly time seems to have gone by is people's feelings of time pressure—how busy do they feel they were over a certain time period? If you feel it's been a busy month or year, you'll report it feeling like it's gone faster, because your memories are of how frantic everything was.

But, interestingly, people also seem to underestimate how busy they felt in the past. As time goes by we forget all of the minutiae that filled our days with flurries of activity and remember just an abstraction of what was going on—the big stuff. Put these facts together and it isn't that time moves faster as we age, but that we always feel like the present is moving faster than the past even if it wasn't. We just have a memory bias that makes it seem like things are always moving faster.

There is one exception to this—if you ask how quick the past decade felt, older people do tend to report it moving faster than younger people. It might be that over such a long period of time, other factors like specific memorable events start to play a role.

There's a saying that for parents "the days are long but the years are short". I can sort of agree with this. The days of parenting can be grueling at times—it's emotionally exhausting to spend hours everyday trying to get a four-year-old to do things they just don't want to do. And it does feel like it was just yesterday that my baby was a baby. At the same time, if I think about my life pre-kids, that feels like ancient history, and suddenly it feels wild to me that I've only been a parent for four years—those four years feel like my whole life.

To me, these contradictions in my own time perception seem to indicate there isn't a single mechanism for retrospective time assessment or our perception of time more generally. We use a mix of heuristics, drawing on our memories, to answer the question of how long some past period of time was. Depending on what aspects of the past I recall, I might think the years have been long or short. My assessments are malleable. At all levels, time perception isn't just a single system, but a complicated judgment based on multiple heuristics.

I find that comforting. If time really did speed up as we age, then by middle age, most of our subjective life would already be behind us. But it seems a week is just a week, no matter how old you are. That's good news for retirement.

Please hit the ❤️ “Like” button below if you enjoyed this post, it helps others find this article.

If you’re a Substack writer and have been enjoying Cognitive Wonderland, consider adding it to your recommendations. I really appreciate the support.

I'm 82 with mobility problems. I am definitely moving slower than I did 10-20 years ago. And time seems to be moving faster maybe because what took 5 (objective) minutes at 72 now takes 10 or more. The whole slowing thing is the bane of my existence. I don't want to spend 10 minutes emptying the dishwasher or folding clothes out of the dryer. I want to zip through the mundane boring stuff of life so I can go read a book. On the other hand, I don't want to live in a pig sty either. So the unread books stack up. Bummer.

Thanks for these ponderings! I think about this too, even more since I've passed fifty. I've come to visualize time as an ocean, or a succession of ponds: each moment holds tremendous depths and when you dive in, that moment can seem to last like forever. But on the surface it has only been one stroke. I love that saying 'The days are long, the years are short'. Parenting provides some really intense, condensed time. The potential to experience time like that is always there (but let's face it, we're often glad we don't have to intensely live EVERY moment)