Please hit the ❤️ “Like” button at the top or bottom of this article if you enjoy it. It helps others find it.

Long, long ago, the world was a different place: phones were only for making calls—they could not, for example, open up a Maps app, pinpoint your location, and give you precise directions to any location you could name.

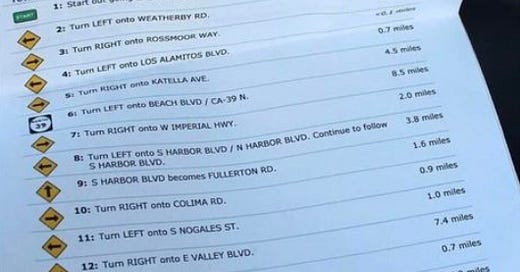

In those dark times, to find how to get somewhere, you had a few options. You could ask someone, but that came with the unsavory consequence of social interaction. Instead, many would visit Mapquest.com from a home computer and print directions off on physical paper.

(Legends tell of a time prior to Mapquest, when people would travel with physical paper maps and need to figure out a route to their destination themselves. I am not a historical scholar so I cannot verify these stories).

The problem with printed off directions is that they're static. They only told you how to get where you were going if you started from the exact location they started from, and only if you made all the correct turns. One wrong turn and, unless you can accurately backtrack, the directions no longer apply.

(Legends also tell of teenage millennials who missed the highway exit that their Mapquest directions instructed them to take, and to this day roam the Earth, doomed to aimlessly haunt the roads in their parents' car).

Directions from Mapquest require that, in this vast 2-dimensional space of the Earth's surface, you start at a very particular location and follow a very particular path. Any deviation from the directions meant they no longer applied. These directions were brittle, unable to "recalculate" the route based on your updated location after taking a wrong turn.

This weird dive into the thin slice of time after internet maps but before smartphones was all a set up for an analogy. You see, I've heard from a reliable source that life is a highway. This source also declared he wanted to ride it all night long, which seems a bit odd since we are all "riding" life all night and beyond, but maybe there's some metaphor there I'm not getting. Anyways, let's take this "life as a highway" thing seriously and talk about life's directions.

High-Dimensional Life-Space

Just as we navigate the physical surface of the Earth, we also navigate life. But life is a lot more complicated than any road system (the roads in Boston excluded). Instead of just "Go left" or "Go right", we have seemingly limitless directions we could go. "Be nicer to people", "Take up running", or "Put all your money in Bitcoin" are all options.

Similarly, where we currently are in life can't be captured with simple latitude-longitude coordinates. If we imagine all of the possible ways two people's lives can differ—their relationships, dispositions, financial circumstances, accomplishments, and so on—there would be, like, a lot of ways to differ. If we're in a linear algebra mood, we could picture each of these ways that we can differ as a dimension in a vast high dimensional space in which each possible person is a single point (just kidding, we can't picture that but we can pretend that we can and look smart for talking about high dimensional spaces).

We can't even communicate where we are in this space—it's a bit of a mystery to ourselves. I know of a lot of ways my life differs from others, but am always surprised to learn new ways my experiences fundamentally differ from other people's. For example, it's surprising to me that some people actually enjoy brushing their teeth with mint toothpaste (you know you're allowed to use Watermelon Blast, right?).

For another thing, if we knew where we were in this space, it would take too long to describe our location on every dimension, exhaustively describing every possible personal disposition and life circumstance we have.

It's also hard to describe our destination. Where do we want to go in life? We might have a general place we would like to get to—we all presumably want a happy and meaningful life. But the paths that could be taken to get there are going to be different for everyone, given the vastly different locations we all inhabit, and so there are different turns and side roads available to us to get there.

It's odd, given these circumstances, that people constantly feel they are able to give us directions. But people love to do just that. We call it advice.

Mapquest Directions for Life

Not all advice is bad. But a lot of it is. And often it's because it's too generic and static.

"Find a niche" is common advice for bloggers and newsletter writers. The logic is simple: specific topics are more likely to grab a particular reader's attention. "Life Reflections by Joe Nobody" won’t seem relevant to anyone; "Reflections on Parenting Toddlers by Joe Toddler-Parent" is going to be highly relevant for a small portion of readers (other parents of toddlers). Narrowing in on a niche increases relevance, and relevance is what makes someone actually click and read your thing.

But for many, "niche down" is terrible advice. If I limited myself to neuroscience, I'd rarely have anything to say—and I’d probably stop writing altogether. Others may not even have a clear niche to begin with. Forcing one before you’ve figured out what you enjoy writing and what resonates can be more limiting than helpful.

For many, they're in a part of High-Dimensional Life-Space where taking a turn down Niche Lane won't lead them to Successful-Newsletterville and will just put them in a direction with fewer interesting sideroads.

"Learn to say no" is helpful for people too far in the "Say yes to everything" dimension, but bad for people who would be better off if they "leaned in" on more professional and social opportunities.

Advice also fails when it's so vague it doesn't even give direction. "Work Hard" is the brilliant advice of none other than Sam Altman. But that just raises the question "How?" What side road do I turn down to get there?

Plenty of productivity gurus try to answer that exact question and end up being overly specific. I suspect the systems these productivity gurus come up with are based on the particular roadblocks they themselves faced on their idiosyncratic journey. Cal Newport recommends scheduling "internet time"—literally scheduling when you use the internet for any purpose. To me, this is nuts—while working, I constantly need to consult resources on the internet and it rarely acts as a distraction. Far from putting me on a freeway to Productivity-Town, the "Schedule Internet Time" path just looks dreary and potholed in my location.

Advice and Optimization

A lot of advice is just people overgeneralizing from what worked for them (or from successful people), taking their view from one tiny point in this vast high dimensional space and assuming it applies to all others.

But some advice is useful. A personal mentor, who knows a lot about your current location, the general landscape you're navigating, and has seen a lot of others traveling through a similar area, might have good insights. And of course, there is some advice that is just helpful for large swathes of people because there are general trends that hold for the majority of the spaces people are in.

So how do we sort out good advice from bad?

I'm self-aware enough to realize giving advice on assessing advice falls prey to the exact same problem I've been griping about—any quick rule of thumb for how you should approach advice is going to ignore the context of whoever you are and where you currently are.

But maybe another analogy can help.

In computer science, optimization algorithms navigate high-dimensional spaces to find the optimal point in the space. Given a point in space, the algorithm can check what the value is, but it isn't able to check all possible points—there's just too many. What they do instead is wander around the vast space. They can see which direction in this vast space currently goes "up" in the value they're trying to maximize, so they'll travel in that direction, and keep taking steps in the "increasing" direction to try to locate the best spot.

It's a bit like (to connect analogies here) being in a car at night, and only being able to see as far as your headlights—you can see which directions slope up or down, but you can't say definitively which road will lead you to the highest point. But if you have to choose a direction, just heading "Up" isn't a bad idea—that's basically what these algorithms do, and they navigate complicated spaces quite well.

A common failure mode of these algorithms is getting caught in a local-maxima—a value that is better than those around it, but is low compared to some other larger maxima. It's like ending up on a small hill, all directions leading down the hill, and so missing the giant mountain you could be on top of across the valley.

So a major feature of these types of algorithms is how they deal with these sorts of local minima. They add randomness. They explore from multiple starting points. They shake things up when progress stalls. Going uphill helps, but if you don't explore, you might miss the mountain.

Advice is telling us we should try a certain direction. Suggesting we take a peek down a certain road isn't a bad thing. Maybe we'll discover things do indeed start sloping up again in that direction. Or maybe we'll find ourselves in a complicated maze of backroads, none of which seem to go up. We can always just shrug and turn back, figuring that those directions don't work coming from our part of town.

The observation that the value of advice is context-dependent isn't new. And that's okay. But maybe these analogies will help someone see advice in a new way, or make someone chuckle. Writing this thing was me heading down a particular road to see where it goes—as is me publishing it. Maybe it will resonate. Maybe not. I can always double-back and head on my merry way. Life is, after all, a highway.

Please hit the ❤️ “Like” button below if you enjoyed this post, it helps others find this article.

If you’re a Substack writer and have been enjoying Cognitive Wonderland, consider adding it to your recommendations. I really appreciate the support.

>A lot of advice is just people overgeneralizing from what worked for them

This is so darn true.

It is amazing so many people have so little empathy.

Love how you built up to the point from the pre-smartphone times.

I still had an A-Z map in my car until last year when I accidentally left it in my old car.

It occurred to me after I realised I hadn't grabbed it that the maps in the book were maybe 15 or 20 years out of date so lots of new roads and routes wouldn't have even been in it.

I think that's very relevant to advice too, some may be old and out of date, but not completely useless.

Great post