Being A Neuroscientist Doesn’t Make You A Wellness Expert

The Rise of the Neuro-Grifting Gurus: Andrew Huberman, Julie Fratantoni, and Dominic Ng

I try to keep things positive in this newsletter, and generally think I do a good job of it. But sometimes you just have to name names and point out the bullshit.

There are a number of people using their neuroscience credentials to give them unearned credibility in the wellness space and proceeding to sell snake oil.

These people are simply grifters, looking to gain influence and make money. They have three things in common:

Using neuroscience credentials to give them credibility in something unrelated

Extrapolating wildly beyond the scientific evidence

Promoting things based on how lucrative or sensational they are, not based on the evidence

By cashing in on the public’s esteem for scientists, these charlatans are making people who share their credentials—like me—look bad by association. It’s an assault on expertise, and more experts should speak up and point it out.

Science Garnish

I’ve said it before, but it bears repeating: Neuroscience is particularly ill-suited as a discipline to tell you how to live. Neuroscience is rarely relevant to lay-people’s understanding of high-level behaviors or how to improve them. And neuroscientists don’t have training in health or wellness—those are the domains of areas like medicine or psychology or exercise science.

Neuroscience primarily studies mechanisms and disorders, not general “brain optimization”. For healthy people, there isn’t much neuroscience that maps cleanly onto wellness advice. This is why the neuroscience mentioned in wellness advice usually only has some vague superficial connection to the underlying advice. The neuroscience is just (to steal a term from

) science garnish on some crusty old bullshit so it can be served up as a fresh new insight supported by Science™.The frustrating thing is, people eat it up.

Studies have shown that non-experts judge explanations as better when they contain irrelevant neuroscience. They call this “The Seductive Allure of Neuroscience Explanations”. Neuroscience sounds fancy, and when people hear it thrown in (mentions of “brain”, “neuroplasticity”, etc.), they assume we have a much deeper understanding of something than we actually do.

To me, this is an indication that we neuroscientists have a duty to better inform the public about the limits of neuroscience and help them understand what it can and can’t tell us. But apparently, to others, this is an opportunity to short circuit critical thinking to gain unwarranted confidence from an audience looking for advice.

They can then use that confidence in dark ways. Let me start with a cautionary tale.

The Household Name Neuro-Grifter

Of course in an article like this, I have to mention the biggest name in neuroscience grifting, a pioneer in abusing credentials to push questionable wellness advice: Andrew Huberman.

Huberman is an enormous name in the wellness arena. He is a tenured neuroscience professor at Stanford. His podcast is regularly ranked the #1 health podcast in the world. And he’s well-known for peddling bullshit.

I was introduced to Huberman via a podcast episode he did on gratitude rituals. I was mildly curious about the evidence behind these, and when I saw a neuroscientist from Stanford talking about it, I figured it would give me a decent evidence-based overview.

The episode was weird. It sure didn’t sound like how scientists talk about research. He gave his own gratitude ritual, gave some superficial neuroscience explanation, and talked up how important it is.

I figured he must just be simplifying for a very general audience, so I checked the episode’s references. What I found was the vast majority of what he said just wasn’t supported by the research. The research was patchy and incomplete, but he had extrapolated wildly and added his own details as was convenient for his story.

It was a familiar grifting pattern: throw in just enough science and then go hog-wild extrapolating and exaggerating to make the topic seem certain and important, no matter how uncertain and unimportant it is.

If this was limited to things like gratitude rituals, that wouldn’t be terrible. The evidence might be patchy and the impacts small, but whatever, exaggerating gratitude rituals probably isn’t harming anyone. But that’s not the only stuff Huberman pushes.

While there’s at least a tangential link between neuroscience and gratitude rituals, Huberman is all too happy to go outside of his field of expertise. He’s given a long podcast on ways to avoid the flu. In it, he downplays the most effective methods that immunologists point to (vaccines) and encourages a bunch of dubious supplements to “boost your immune system” (boosting your immune system is not really a thing).

By telling you something different from the obvious mainstream advice, he’s saying something that feels actionable. Everyone’s heard they should get vaccinated and wash their hands, that’s nothing new. But by telling you to take supplements or go in the sauna or cold plunge, his advice sounds fresh and new. It helps him stand out. But it sounds fresh and new because no one is recommending this stuff—because there’s no good evidence it’s effective. And by attaching himself to the extremely lucrative supplements industry, he gets juicy sponsorship deals.

This is just a small sample of Huberman’s sins. I don’t want to write a full take-down of Huberman. People can and have written lengthy articles doing just that. I’m just pointing to him as a cautionary tale of a neuroscientist abusing their credentials to gain people’s confidence, and using that confidence to peddle snake oil.

Huberman is a crank, but a big mainstream one, and if I got mad about every mainstream crank I’d spend my whole life mad at weirdos who decided to trade their conscience and credibility for a cheap buck.

What really motivated this post was watching in real time as neuro-grifters grow and thrive in my little digital backyard: Substack.

Julie Fratantoni

Fratantoni started on Substack in early 2024, and I remember being excited the first time I saw her account—another cognitive neuroscientist! Yay!

What’s been depressing is seeing what’s happened since she’s gained popularity.

Of course there is the abuse of neuroscience. She frequently mentions neuroscience and neuroscientific terms despite their lack of relevance, to activate the “seductive allure of neuroscience” mentioned above.

More worryingly, she has a habit of downplaying traditional medicine in favor of general wellness advice.

General wellness stuff, like getting enough sleeping and exercise, are great for maintaining general health. But for someone with an actual pathology who has been prescribed an antidepressant, telling them (as Fratantoni does) “No antidepressant is better than EXERCISE” isn’t just bad advice, it’s dangerous. Whether someone’s depression treatment involves a drug intervention or not is a judgment that should be made in connection with a doctor treating them for the disorder, not an online wellness influencer.

Amusingly, she blocks critics that point this out to her, as my wife learned firsthand.

As critical as I am of Fratantoni, I have to hand it to her: she’s got a knack for marketing. In 2 years, she’s grown to having hundreds of thousands of subscribers. But this growth has come with a worrying trajectory.

If you look at her earlier archive, she actually wrote some decently nuanced stuff. For example, back in March 2024 she wrote about lion’s mane, a popular “nootropic” (brain boosting) supplement, and concluded:

There doesn’t seem to be very compelling Level 1 evidence for improving cognitive function in healthy individuals. I could only find one paper with healthy adults.

Pointing to the uncertainty like this is great! Scientists should do more of this!

Contrast that with a more recent article that’s basically just a long list of affiliate links (affiliate links are sales links, where the linker gets a sales commission—i.e. she is making money if people buy). The products she’s pushing include dubious supplements and, more damningly, grounding shoes.

The grounding shoes deserve a bit of elaboration. Grounding (or “earthing”), at a high-level, is the idea that walking outside in your bare feet is good for you. Sounds reasonable enough, right? Maybe we all would be better off occasionally kicking off our shoes and feeling the grass and dirt on our feet.

But grounding isn’t about the tactile feel of nature between your toes. It claims that when we walk barefoot, the Earth gives us negatively-charged electrons that neutralize harmful positively-charged free radicals. Since walking barefoot in contact with the Earth is so rare nowadays, the idea goes, many of our health problems can be solved by just getting back in contact with the Earth and allowing the electrons to flow.

Hopefully I managed to make that sound charitable, because the idea itself is laughable bullshit. We aren’t insulated from our environment—we freely exchange electrons with everything we touch. Ever have a build-up of static electricity? Ever have that build-up discharge in a shock when you touch something or someone? That’s an exchange of electrons. The Earth isn’t the only source of electrons and we certainly are not living lives insulated from them.

Implausible physics aside, there’s no evidence of the underlying claim that our bodies are lacking electrons or made better by getting electrons. Free radicals aren’t neutralized by something as simple as an electron, they’re neutralized by complex molecules (antioxidants).

Neither the physics nor the biology of “grounding” make any sense. It’s mystical “earth healing” magical thinking, dressed up with talk of electrons to make it sound sciencey.

Why would anyone perpetuate this weird pseudoscience? Because it allows you to sell junk. Grounding mats, grounding sheets and pillowcases, and, apparently, expensive “grounding shoes”—shoes you can wear that keep you “connected to the earth”.

Anyone with a modicum of skepticism or science understanding would clock grounding for what it is—a scam. I’ll leave it to the reader to decide what that says about Fratantoni.

“As A Neuroscientist…”

The whole reason I’m writing this article is because people keep sending me messages complaining about Dominic Ng’s Notes. He starts off almost every Note with “As a neuroscientist…” and then says something generic that has nothing to do with being a neuroscientist.

This is just generic wellness advice with “as a neuroscientist” tacked onto the front. This presents the advice as if the expertise is relevant, even though it isn’t.

Ng’s sins are much smaller than Fratantoni or Huberman. The majority of Ng’s articles are pretty tame advice. To sleep well, go to bed at a consistent time, and only use your bedroom for sleep. To do hard things, start small. I find the suggestions bland and obvious, but that’s kind of the point—most things that actually work are going to be bland and obvious. The alternative is to be like Huberman and point to sensational stuff that probably doesn’t work.

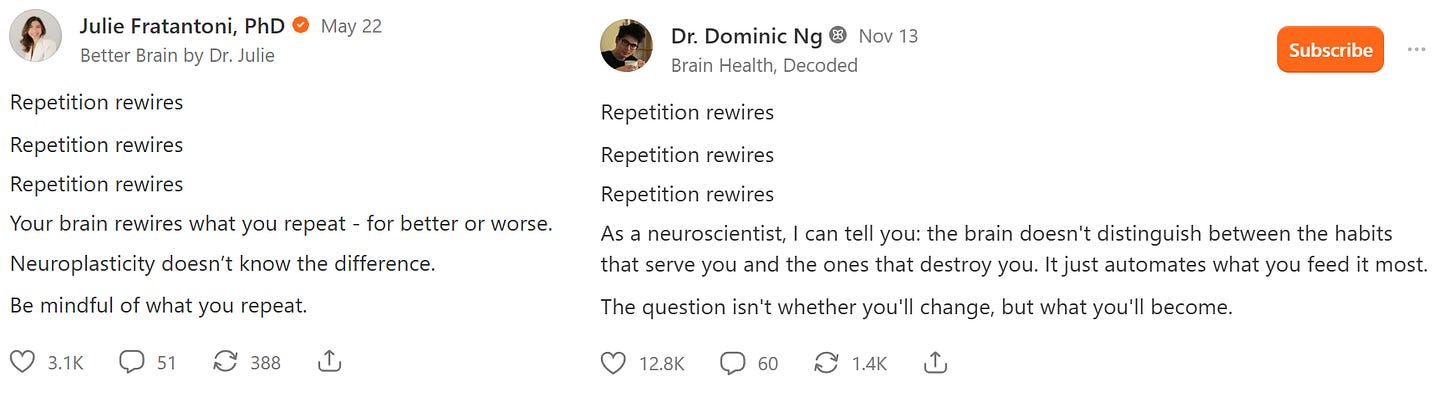

But to spice up his bland and obvious advice, Ng likes to superfluously mention neuroscience. This happens in his articles—often the only place he mentions anything neuroscience related is in the title—but it’s more comical in his shortform Notes.

I could go on and on with more examples—from Ng and Fratantoni—of irrelevant neuroscience tossed into what would otherwise be bland advice, but hopefully the pattern is clear enough.

Ng mentions neuroscience everywhere, not because it’s relevant, but because it’s sexy. It gives the impression of relevance, mostly due to the lack of public understanding of the severe limitations of neuroscience.

More dangerously, like Fratantoni, he has a habit of pitting generic health advice against medicine. He makes broad blanket claims like “The best thing for your brain isn’t a pill” and instead suggests sunshine and walks. By framing general healthy behaviors as in opposition to medical interventions, he is discouraging people from effective treatments. Many people already feel shame about taking medication to help them with their disorders (especially psychiatric ones), and this doesn’t help. You can encourage general health and wellness without pitting it against medication a doctor is prescribing.

What’s especially weird about Ng is, while he’s just a neuroscience grad student, he also has a medical degree. I would think the medical degree would be way more relevant to giving health and wellness advice than an incomplete neuroscience degree. But again, Ng has grown his audience very quickly—clearly he knows that neuroscience wellness sells in a way traditional, actually-relevant expertise doesn’t.

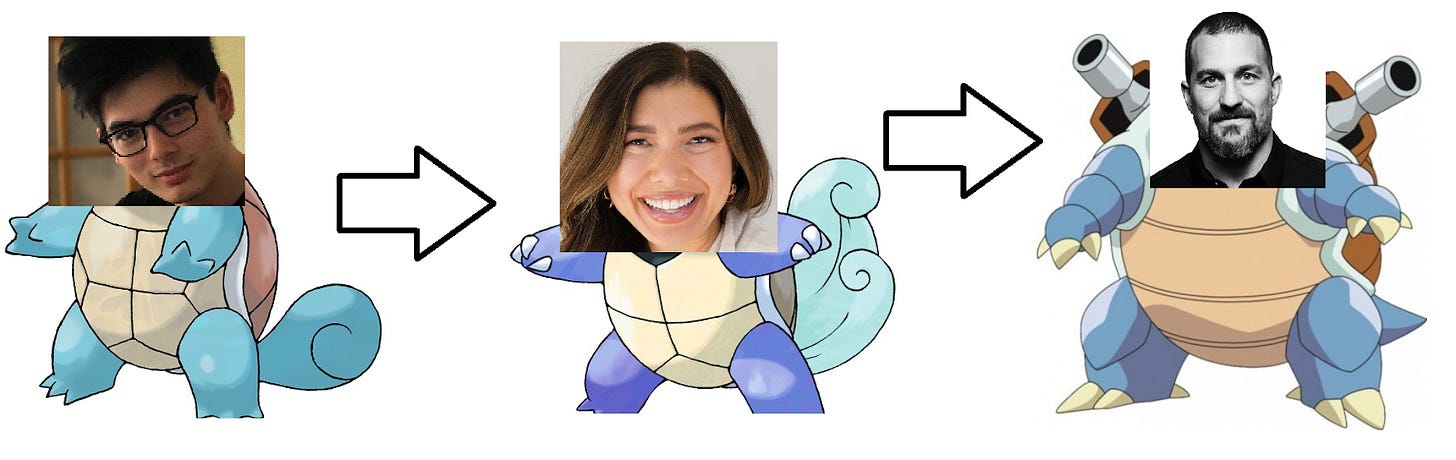

I have a deeper worry, though. The order in this article might be seen as a sort of reverse-order of a Pokemon evolution. If I’m right that Fratantoni started out being reasonable and went corrupt once she gained an audience, there’s a worrying possible future here.

Hell, Ng even seems to be ripping off ideas from Fratantoni:

As far as I know, Ng has not peddled dubious products that he earns money from. He has mentioned supplements, but with caveats. Interestingly, his recent article on supplements even echoes some of Fratantoni’s balance above about lion’s mane:

Lion’s mane mushroom shows early but promising evidence — small studies suggest it may support cognition and mood, though the research is still limited.

I’m by no means endorsing Ng or that article, but he’s at least saying things that are defensible, not the usual wild wellness exaggerations.

My worry is what comes next. He’s shown he’s not above misusing neuroscience if it benefits him. What happens if a supplement company comes and offers him a bit of money? If he thinks there’s some evidence that lion’s mane works, why not take the money? Sure, it would mean laying it on a little thicker than he otherwise would, but not necessarily saying anything he thinks is outright wrong.

Then his audience gets bigger, and the offered checks follow suit. Before you know it, through a series of tiny compromises following the incentives, he’s hawking his own proprietary blend of Ionized Horse Piss™, guaranteed by Neuroscience™ to increase the functioning of your Neural Action Potentials™.

I hope that doesn’t happen. Step back from the ledge, Dr. Ng. And please, cut out the fucking “As a neuroscientist” Notes.

Being a neuroscientist doesn’t make you a wellness expert

The term “con artist” comes from the term “confidence artist”. The idea is the con artist gains the victim’s confidence before swindling them. By using something poorly understood by the public (neuroscience), neuro grifters are able to gain unwarranted confidence.

The general public has this perception that we neuroscientists know some stuff. The truth is, the brain is generally a mystery. Its connections to health and behavior, especially in non-pathological cases, are poorly understood. There’s no simple advice that’s going to unlock the real power of your brain. Trying to understand how to live your life better through the poorly understood mechanisms of the brain is a fool’s errand.

Not to say there isn’t anything meaningful you can say about the brain and health. There’s plenty of research that provides evidence of that generic healthy stuff like exercise, sleep, and diet, impact certain brain measures and improve cognitive function or reduce risk of neurological diseases.

The trouble is, it’s mostly, like I said, generic healthy stuff. It isn’t that interesting to provide advice for brain health that ends up being the same advice given for heart health and general wellness.

So what should you do if you come across some wellness claim that contains neuroscience? My main advice would be treat it with increased skepticism. Ask yourself what evidence is actually being provided.

Try removing the neuroscience from it and seeing if it holds up. Remove mentions of “brain”, “nervous system”, “neural circuits”, “neuroplasticity”, and replace them with what seems to be implied. Has the author provided evidence for the implication? Have they offered any evidence at all?

Better yet, if the author is using neuroscience terms and it seems at all different from generic wellness advice, you can probably just assume it’s at best an exaggeration. The vast majority of the time you’ll be right.

Great article, thank you. "As a linguist", I can confirm that words matter. A lot.

This is by far the most honest and much-needed post I have read. I don't know much about Julie Fratantoni, but I completely agree about Andrew Huberman and Dominic Ng. Most of the neuroscientists are trained in a very niche topic, and even if they have a wider understanding of different topics, it's wild to have an authoritative stance on it. It's particularly amusing that you grow a mass following by using "Neuroscientist" as if it's supposed to add credibility to you. As you add, people use it to grow their following, become famous, and make quick bucks.