Did I Do That?

Free Will and Our Sense of Agency

A recurring theme of this newsletter is the hidden mechanisms of our minds that shape our experiences. We have more than 5 senses but overlook how much the others contribute to our day-to-day lives, we don't think about the complexity of the processing our senses involve, and we forget how much of what we see is based on what we know.

This week, we're going to look into our sense of agency. What hidden mechanisms are behind the feeling of initiating and causing actions, and what do they mean for our conception of free will?

"Did I Do That?"

When I pick up a pen and draw on paper, I feel like I'm causing ink to appear on the page—which, of course, I am.

But sometimes it's less clear that we're the causes of things. We press the pedestrian crossing button, and shortly thereafter the pedestrian walk sign turns on—did we cause it? Maybe. But some pedestrian walk buttons, like most in New York City, have been decommissioned. We could be pushing buttons that do nothing, but feeling like we caused the walk sign to turn on because it changed shortly after we pushed the button.

There are cases where we are the cause but don't think we are. Dowsing rods, for example, have been of interest to people for centuries because their movements seem so counterintuitive. The rods magnify slight movements, making it seem like they are moving on their own, despite the movement being caused by the holder.

Ouija boards are another fun example—the indicator moves around the board, and no one feels they are the ones doing it (or at least, no one admits they do). The indicator is driven by the combined unconscious movements of the participants, but no one feels responsible for the movements, presumably because there are other potential sources of the movement: other people (or a sPoOkY gHoSt?! 😱).

Daniel Wegner used the Ouija board phenomenon in a clever study trying to tease out how we infer when we were the cause of an event. Study participants put their hands on a device that (they were told) moved a cursor around a screen, but another person had their hands on the device as well—like a Ouija board indicator. The cursor moved around and stopped on certain images on the screen. The participant also had headphones on, which would say words to them but not the other person. These words matched the images on the screen—things like common animals or household objects.

The trick is, the participant wasn't actually controlling anything. But sometimes, in a pre-choreographed event, the word that was played over their headphones matched the image the cursor stopped on right after.

Participants rated how much they felt they had intended the cursor to stop where it did. The researchers found that, despite the participants not being in control of the cursor at all, they felt that they had intended it to stop if they had heard the word related to the image the cursor stopped on just prior to the cursor stopping (so hearing "swan" just before the cursor stopped on the image of the swan).

Wegner argues based on studies like this that our sense of causal agency is inferred from three things: a thought needs to come before the action, the thought and action need to be consistent, and there shouldn't be obvious competing causes. By manipulating each of these factors, you can manipulate one's feeling of having caused an outcome.

It might seem odd that we need to infer whether we've done something or not—surely, since we're the ones that have done it, we should know. But having done something doesn't mean we get a feeling of having caused it "for free". The brain needs to figure out we caused it in some way.

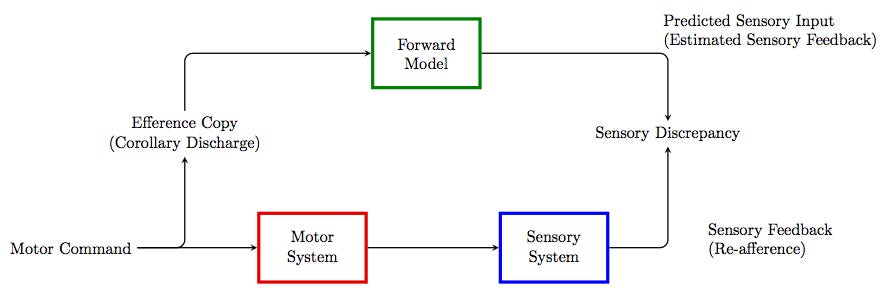

Even something as simple as moving our arm involves brain mechanisms that track whether we caused the motion, so we can distinguish a voluntary movement from being moved by an external force. Our brains generate a copy of the motor command (called an efference copy) to predict what should happen as a result of that signal. It's what allows us to distinguish between the world shaking and us moving our eyes around. It's also thought to be why we can't tickle ourselves—the efference copy allows us to predict what we'll feel when we attempt to tickle ourselves, and "subtract out" that expected sensation.

Our brain's predictive mechanisms are at work for something as simple as telling when we're the one moving our arms, and more complex inferences are involved when we cause effects through indirect means.

Just like with our senses or our memories, the ubiquity and immediacy of the feeling of having caused something can hide the complex mechanisms that generate that feeling.

Threatening our free will

Wegner's work addresses questions about how we infer our agency. Next let's look at an experiment that investigates the formation of our intentions to act: Libet's (in)famous experiments.

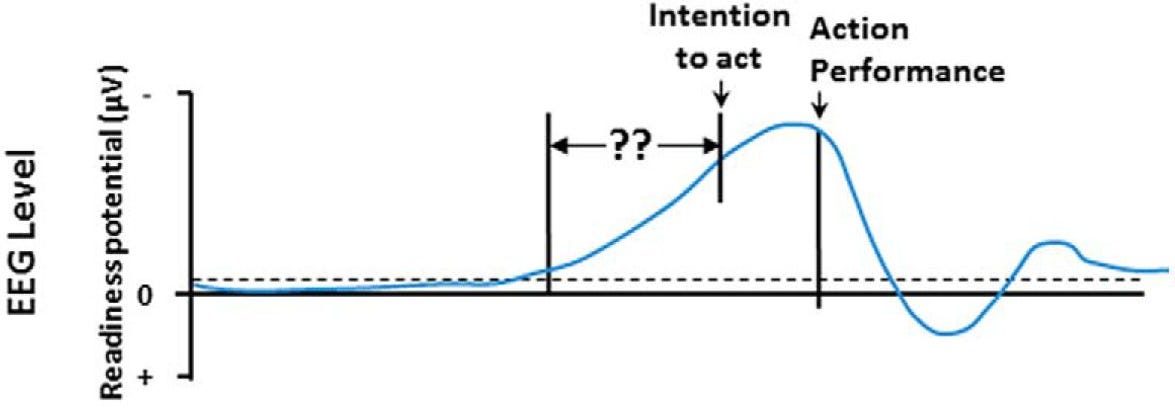

In 1983, Libet performed a simple experiment. He had subjects come in, sit and look at a clock, and move a finger whenever they wanted to. The subjects were asked to remember the time on the clock when they decided to move their finger—a special clock that allowed sub-second telling of time. While subjects performed this task, Libet recorded their neural activity.

The big shocking conclusion Libet came to was that there was ramping activity in the neural activity prior to the time people reported their intention to act. In other words, their brain seemed to be preparing to act before people formed the intention to act.

Much has been made out of this little finding. Philosophers have written lengthy papers and book chapters on it and scientists have done dozens of follow-up studies. There's a lot to unpack about this study, including various methodological and interpretation issues that I'm not going to get into here.

But to me the important question is: should we have expected anything different?

Finding brain activity that precedes our intention to act seems like it might undermine the authenticity of our intentions. But think about what it would mean if there wasn't anything—physical or otherwise—preceding our intention to act. That would mean the intention just popped into existence, without any influence from anything else. Our intentions wouldn't be grounded in who we are or reasons for action. It would reduce our intentions to random events.

I want my intentions to come from me. Libet's task was deliberately minimal, isolating action away from anything else, removing the reasons we usually act. These sorts of actions typically are unconscious. In real life, important actions aren't so arbitrary. When action does matter, I want there to be preceding causes: my beliefs, thoughts, desires, and everything else that makes up who I am.

In that sense, the idea that Libet's experiment seems to show brain activity preceding the intention to act isn't threatening to the idea that I am the author of my actions. I should hope there are preceding causes to my intention to act—I just want them to be the right kind, the structured motivations and reasons that make me who I am. It shouldn't matter whether the properties that make me who I am are encoded in the brain's synapses and activity or in ineffable soul-stuff. Either way, I want those things to be part of the causal chain leading to my actions.

Wegner’s work on the feeling of will and Libet’s experiments on the timing of intention both point to the same thing: that willing is a process, shaped by unconscious mechanisms. Our feeling of causing something involves mechanisms and inferences, and it's possible for us to get it wrong—to feel like we've caused something we haven't. Similarly, there are various unconscious processes preceding our conscious intentions to act.

That doesn’t make the feeling of conscious will illusory, or the conscious intention itself superfluous. It just means, like many other aspects of our experience, it's more complex than it might seem at first glance. We can still have free will in a universe determined by causes. Agency isn't something that floats free from causation, but it's constructed from the often invisible mechanisms that make up who we are.

Please hit the ❤️ “Like” button below if you enjoyed this post, it helps others find this article.

If you’re a Substack writer and have been enjoying Cognitive Wonderland, consider adding it to your recommendations. I really appreciate the support.

Nicely written piece! Thanks :)

I know many people have criticisms of the Libet experiment, and other related experiments. My concern about it is that it conflates free will with conscious awareness. We know from perception studies that consciousness takes a few hundred ms to build (possibly corresponding to 1-2 alpha cycles or one theta cycle). It seems possible to me that free will does exist, but that our conscious awareness of it takes some time to ramp up.

"Will and intellect can form habits of thought and will. We are responsible for forming our habits and even when acting according to habits we are acting freely."

- William James