Please hit the ❤️ “Like” button at the top or bottom of this article if you enjoy it. It helps others find it.

Imagine getting a nice, clean drinking glass and pouring about a mouthful of fresh, cold water in it.

Now imagine spitting in it and drinking the contents.

Well, we just lost half our readers, but for those who are left, that was probably pretty gross to think about, right?

That's super weird! We swallow the saliva in our mouths all the time. Why is it gross to do the same thing but after that saliva has been in a clean cup? If we drank the water in the cup, it would be mixed with the saliva in our mouths anyway, why does it matter if they were mixed in the cup instead?

I originally read about this saliva example in Bruce Hood's book The Science of Superstition, many years ago.

It made me mad.

I thought of myself as a rational person. But I couldn't help myself from gagging when I thought about drinking my spit. I couldn't explain this reaction, there were no rational explanations on why it differed from swallowing what was in my mouth. It was just gross.

Saliva isn't the only bodily fluid that evokes this disgust reaction in most people. We're usually fine sucking the blood out of a cut. But sucking our own blood off of a (previously sterile) bandage? No thanks.

Once our bodily fluids are external to us, they become gross to consume. Things that are internal, that are still a part of us, we aren't grossed out by.

There's an interesting exception to this—loved ones. I would be fine sucking the blood out of one of my toddler son's cuts. I'm fine when my kids give me slobbery kisses, leaving a wet spot on my cheek, but would be repulsed by the idea of having them pour the same quantity of saliva on my cheek from a glass they had filled with drool.

We won't discuss other bodily fluids since my mom reads this (hi mom), but suffice to say there is a similar pattern between certain other fluids sexual partners might encounter.

Psychologists that study disgust suggest two mechanisms involved in our feelings around bodily fluids.

First, we find certain substances disgusting. They tend to be animal products, bodily fluids, and spoiled food. There's a pretty good reason to avoid these things: they're likely to carry pathogens. There's cultural variation in exactly the substances we find gross, but the general pattern holds.

But we have a lot of this gross stuff inside of us. Obviously it's fine for there to be saliva in my mouth. So second, there's a judgment of when something crosses the border from being internal to us to external.

Hence the spit in the cup being gross. It's just a couple of dumb heuristics. A bodily fluid and external to me? Gross! I know the reasons for the heuristics, and know that they don't apply in this case. My spit in the clean cup won’t make me sick.

But knowing about these two mechanisms and their purpose, I still can't overrule them even though I know they don't make sense in the spit-in-cup case.

Sure, I could force myself to drink my spit if someone offered me money, but I can't convince myself it isn't gross (okay, maybe if I stuck to some training regimen where I drank my spit everyday I could eventually change my revulsion through repeated exposure but, like, that's a super weird hobby. I'm only writing this parenthetical because of some imagined reader making this objection, so if you're that reader please repeatedly drink spit to prove me wrong).

The point I'm trying to make is that our behaviors are often driven by funny quirks like this, that we might not be able to justify but that are a part of us nonetheless.

Moral Judgments

Since we already are making this article gross, I might as well throw this in:

Julie and Mark are brother and sister. They are traveling together in France on summer vacation from college. One night they are staying alone in a cabin near the beach. They decide that it would be interesting and fun if they tried making love. At the very least it would be a new experience for each of them. Julie was already taking birth control pills, but Mark uses a condom too, just to be safe. They both enjoy making love, but they decide not to do it again. They keep that night as a special secret, which makes them feel even closer to each other. What do you think about that? Was it OK for them to make love?

I know what you're thinking. First, drinking bodily fluids from a cup, now incest, this article really has it all.

The above is a vignette used in a moral psychology experiment. If you're like most people, you don't think the incest above was okay (though the study was run before Game of Thrones came out, so maybe the depiction of the incestious Lannisters as caring and relatable humans has changed some minds).

A totally normal and loving incestuous relationship (except that time he raped her in front of her dead child, that was a bit iffy)

But asked to defend why it isn't okay, people get weird. They'll point to the problems with inbreeding, but the siblings used two forms of birth control. Some researchers have argued based on this that the moral judgment comes first, and then we try to rationalize it later.

Other researchers disagree, pointing out that many participants point to potential harm to the relationship (and don't buy the story that there wasn't harm done). This theory is bolstered by the fact that people's judgments of the immorality of the siblings correlates with their judgments of possible harm.

This reminds me a lot of the research on other forms of biases in decision-making: we have an unrealistic scenario, and people respond in ways that seems kind of irrational, but when you pick at it a bit, it seems either not that irrational or at least a heuristic that when broadly applied in the real world leads to good results.

In the real world, if we found out two people were engaging in incest, we would think there was something deeply wrong with them. Anyone breaking such a strong taboo probably lacks the regard for other social norms—a key trait of sociopaths. The idea that the impact on their relationship was uncomplicated, positive, and that they could be sure of this before they engaged in the activity all seem dubious. So we feel this must be wrong, and there's good reason for that feeling! Yet people often have trouble articulating why, and many of the articulated reasons don't make sense. We feel more than we reason that it's wrong.

Just like with the saliva-in-cup, the heuristics have good reasons to exist. But the mechanisms giving rise to the judgment seem disconnected from those good reasons, and we come up with ad hoc explanations to justify them instead.

These aren't isolated examples. Let's look at a slightly less gross situation.

Trolley Problems

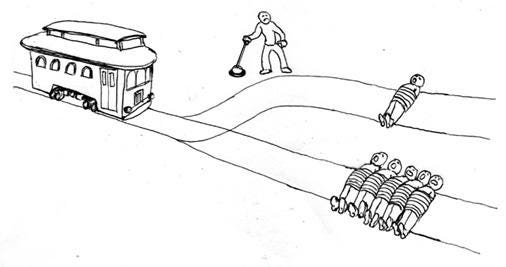

In case you're neither terminally online nor a philosopher, here is a description of the Trolley Problem: Imagine a trolley (I think that's British-talk for a streetcar) is barreling down a track towards five people who for some reason are tied to the track. The trolley will run over and kill those people. You are at a switch that would redirect the trolley, but it would redirect the trolley down another track where one person is tied up. Do you pull the switch?

A good portion of people say "Yes". One person dying isn't as bad as five.

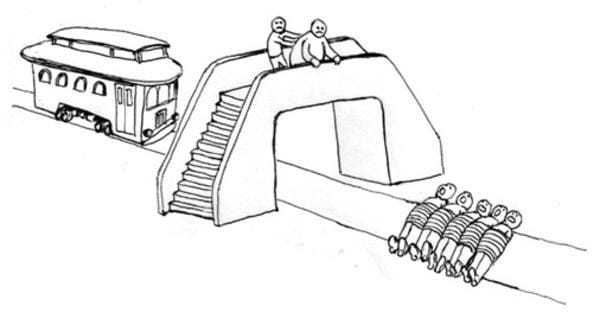

Now consider a different scenario. The trolley is barreling down the track. You are standing on a footbridge above the track, next to a plump man who is leaning over the bridge for some reason. You could give the plump man a good shove and he would land on the track, and you're sure his heft would stop the trolley, again sacrificing one person to save five. Do you do it?

People have a different reaction to this version, generally being much more averse to shoving a person off the bridge than pulling the lever. But from a purely utilitarian perspective, this is hard to explain—the consequences seem the same between the two cases, sacrificing one life to save five.

In fMRI experiments, people seem to use different parts of their brains for the two situations—the amygdala's activity tracks the emotional reaction to the scenario, whereas the prefrontal cortex (specifically the ventromedial prefrontal cortex) seems associated with utilitarian judgments and mediating the emotional response to produce an "all things considered" final judgment.

The authors argue for a two-system view of moral judgment (sound familiar?). I'm not sure I'm sold on the idea, but regardless of your thoughts on it, it seems to indicate my broader point: the footbridge version of the trolley problem and the incest problem seem to be cases where one part of us, a heuristic or emotional reaction, is very strong, for reasons that we find hard to articulate. Our explanations of why we would choose one feel a bit like ad hoc explanations, rationalizations to paper over the fact that we're acting a bit weird here.

Confabulation

I'm trying to chip away at the idea that we're unified creatures. We all know we can feel conflicted over certain decisions. But the examples above show not only conflict, but seem to pit hard-to-articulate gut reactions against reflective reasoning on issues we think of as pretty central to ourselves—moral judgments.

I suspect the above cases are mostly driven by heuristics against breaking certain taboos. Though we can rationalize these after the fact (much like I think our heuristics in non-moral decision-making are broadly pretty rational), I think there is a disconnect between our conscious understanding of those reasons and the heuristic driving the reaction.

Let's look at a more extreme example where the explanation of an action is divorced from what drives the action.

To alleviate cases of intractable, severe epilepsy, some patients have their corpus callosum—the bundle of fibres that connects the left and right hemispheres—severed. This means the left and right sides of their brain can't communicate (or at least, much less so than an intact brain).

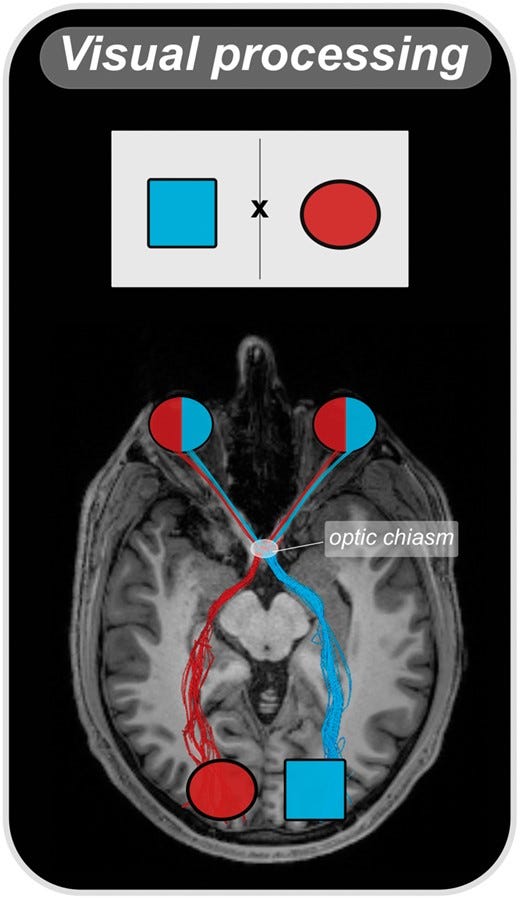

This opens up opportunities for all kinds of cool experiments. Each hemisphere receives visual information about one side of visual space—the left side of the brain receives information about the right visual field, and vice versa. With the communication between the hemispheres disrupted, this gives you a way to present information to only one side of the brain.

Since each hemisphere also controls only one side of the body (the left controls the right and vice-versa), this allows you to also get responses from each hemisphere of the brain by getting it to point.

In most people, the left hemisphere of the brain is where language is produced. If you ask a split brain patient a question, you're getting a response from the left hemisphere.

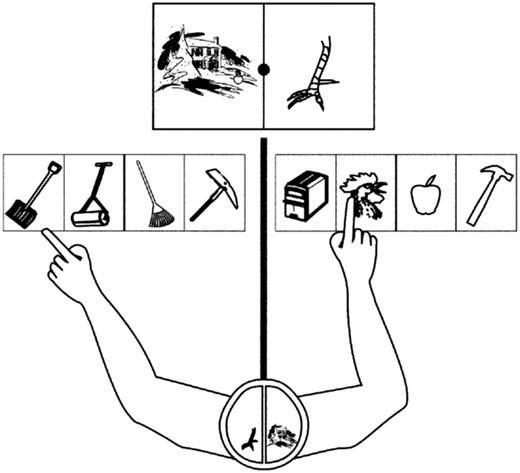

This is the set-up for a classic experiment. Researchers showed the left hemisphere one image, the right hemisphere another, and asked the patient to point to related pictures.

In a telling example, one patient was shown a snow scene on the left and a chicken claw on the right. The patient's left hand pointed to a shovel to go with the snow scene, and the right hand pointed to a chicken to go with the chicken claw. Both obvious choices given the picture shown.

Then the experimenters asked the patient why they had chosen these items. The left hemisphere, knowing only that they had seen a chicken claw and had pointed to the shovel and chicken, made up a story: "The chicken claw goes with the chicken, and you need a shovel to clean out the chicken shed."

It seems obvious what's happened here—the left-hemisphere has reached for some kind of explanation to tie together their actions, and found one. The patient isn't aware that they're confabulating, they really believe they know why they acted the way they did.

This kind of attempt to construct a plausible story to cover an apparent gap in behavior isn't just a feature of split-brain patients. People with various memory disorders sometimes confabulate—they'll "recall" something, whether a personal story or a historical one, that sounds plausible but is false. As our memory mechanisms fail, we seem to make up plausible but false stories. We seem to have mechanisms to make things make sense, even when we don't know the answer, and we engage these mechanisms without knowing it.

Which raises the question—how often are we actually aware of the real determinants of our actions? How often is there some powerful factor at play that we lack insight into, but we tell a plausible story that papers over that gap in our self-knowledge?

My opinion is we're made up of a bunch of mechanisms and systems, some of which we have some insight into, some of which we don't. Many of our behaviors involve input from many of these different mechanisms. When we try to make sense of our own behaviors, this is an active process—we don't just, by virtue of being ourselves, know which of our mechanisms are at work. And I suspect this active process usually works decently—most of the time we probably have an okay idea of at least the broad shape of our motivations. But I know I've often, after cooling down after an emotional moment, realized I had more motives than I realized in the moment. And it's easy to imagine that there are times where I don't have this level of self-reflection, or where even with reflection the true motivations would remain unknown to me.

Anyways, time to wrap this up. I'm going to go enjoy a nice warm glass of spit.

Please hit the ❤️ “Like” button below if you enjoyed this post, it helps others find this article.

If you’re a Substack writer and have been enjoying Cognitive Wonderland, consider adding it to your recommendations. I really appreciate the support.

“The real trouble with this world of ours is not that it is an unreasonable world, nor even that it is a reasonable one. The commonest kind of trouble is that it is nearly reasonable, but not quite. Life is not an illogicality; yet it is a trap for logicians. It looks just a little more mathematical and regular than it is; its exactitude is obvious, but its inexactitude is hidden; its wildness lies in wait.“ Chesterton in his autobiography Orthodoxy

Fascinating. Regarding the fabulation involved in brain-separated states: I was reminded of the Roman Seneca, who wrote in Letter 50 about a poor woman who was losing her sight, but instead blamed poor lighting in her room - this turned out to be the first recorded account of Anton's Syndrome, which combines vision/hearing loss with cognitive inability to recognise same, instead generating explanatory fabulation. Seneca makes the metaphorical point that we're all subject to a range of 'blind spots' and exculpatory fabulation - as you also observe!