How I went from a bad writer to a slightly-less-bad writer

Pretentious Utilization of Verbiage and Making Things Simple Takes Work

This is another set of two mini-essays—connected by a theme, but separate enough that it didn't make sense to make them into one. The theme this time is about writing and clear communication, and the lessons I learned as a grad student who was not good at either.

Mini-Essay 1: Pretentious Utilization of Verbiage

When I started my PhD, I had the experience many grad students do: my advisor replied to my emails with short, to-the-point messages with no niceties. They contained no capitalization or punctuation, but plenty of typos.

Meanwhile, I was feeling like a complete imposter. I was being allowed to supervise the research of undergraduates despite the undergraduates all having more science training than me. My degrees were in computer science and philosophy—I still suspected my admission to a "Brain and Cognitive Sciences" program was some sort of clerical error.

You better believe I did everything possible to appear "smart". You wouldn't catch a grammatical or spelling error in my emails, let alone my scientific write-ups.

Despite this meticulousness, my writing sucked. High school had taught me that science was written in an impartial, "academic" style. You were supposed to use passive voice and technical scientific terms. In the results section, give an impartial report of the findings—no attempting to interpret the findings.

Of course, I had to unlearn all of that because they're all terrible writing habits if you want anyone to read and understand your research. But to unlearn it, I first had to get over my imposter syndrome. Technical terms and impersonal language made what I was saying sound smart and scientific.

My advisor wasn't afraid of looking dumb—he had a PhD, multiple scientific grants, papers published in some of the most prestigious journals, and a lab at a top research university. No one was going to question his intelligence because he didn't start an email with a capital letter.

When it came to writing papers, my advisor was excellent. He knew how to explain things clearly and in simple terms to make the papers broadly accessible. He would question why anyone would ever use a word like "utilize" when "use" would work. He would remove technical terms and acronyms whenever possible. He made sure there was a central grounding message to the paper, and that the ideas flowed logically from one to the other.

It took me a while to become confident enough to improve my communication. When I had a few papers under my belt, I had a couple of other professors in the department tell me they were impressed by how much I had accomplished. Suddenly I didn't feel the need to be so pompous in writing. Lack of punctuation was fine in quick emails.

Unfortunately by then I was near the end of my time in grad school. I left academia still terrible at writing. It took years of work for the lack of self-consciousness to work any magic. Hopefully now my writing is less terrible. At the very least, it's made me okay adding images of Space Sharks or a cartoon fat lobster to my articles.

I know it's generalizing and is often just a stylistic copying, but to this day I see the use of overly technical language as a lack of confidence. If you fear you'll look dumb putting things in plain English, it signals to me you don't have confidence in yourself or your ideas. In which case, why should I?

Mini-Essay 2: Making things simple takes hard work

The easiest reading is damned hard writing

Clear communication—both verbal and written—is a frustrating skill to develop because it seems so easy. Just say the thing you want to say!

When we come across clear writing, there's no stumbling over awkward words. The idea is crystal clear. This fluency can trick us into thinking the writing was this seamless too. And once we see how to convey something clearly, it's easy to reproduce.

This all hides how hard it is to actually write clearly! As much as I roll my eyes at the simplifications in pop science books, I have to admit, I'm mostly just trying to feel superior to those plebs that need things simplified. In actuality, many popular science authors are extraordinarily good at clear communication. And it takes a hell of a lot of work to do it.

I didn't understand this when I started my PhD. In grade school, I had always just written an essay in a single draft and submitted that. I didn't know what else could be done—I wrote the thing, what more could I do?

Writing scientific papers is high-stakes. You're writing up the results of months or possibly years of data collection and statistical analyses. If the writing obscures your findings, you've done a massive disservice to all the work you did. Spending a bit more effort on the writing can dramatically multiply the impact of the paper, just because you've made the ideas clearer and more accessible.

My PhD advisor would have me brainstorm dozens of titles for papers. Sometimes one of the titles would have some promise but not quite fit, so it would act as the seed for another round of brainstorming titles. In the end, a single title was chosen, and the rest discarded.

When I started writing fiction, I ran into this same brainstorming advice—for example, in the Death of a Thousand Cuts podcast's 100 day writing challenge, most of the exercises involve just coming up with lists of things. If you're unsure how to proceed, write a list of possibilities. Come up with a ton of ideas even if you'll only use one. Most of the work of writing never sees the light of day.

Communication is a skill that can be developed. But in my experience, the best way to develop it is to put in a bunch of hard work editing your writing. You'll gradually develop your ability to give a clear explanation in the first place, but more importantly, you'll gain an ear for what clarity sounds like. When you look at a sentence you wrote, and can see a suggested change and realize it's a tighter, clearer sentence, the message rings much clearer than seeing dozens of examples you didn't write.

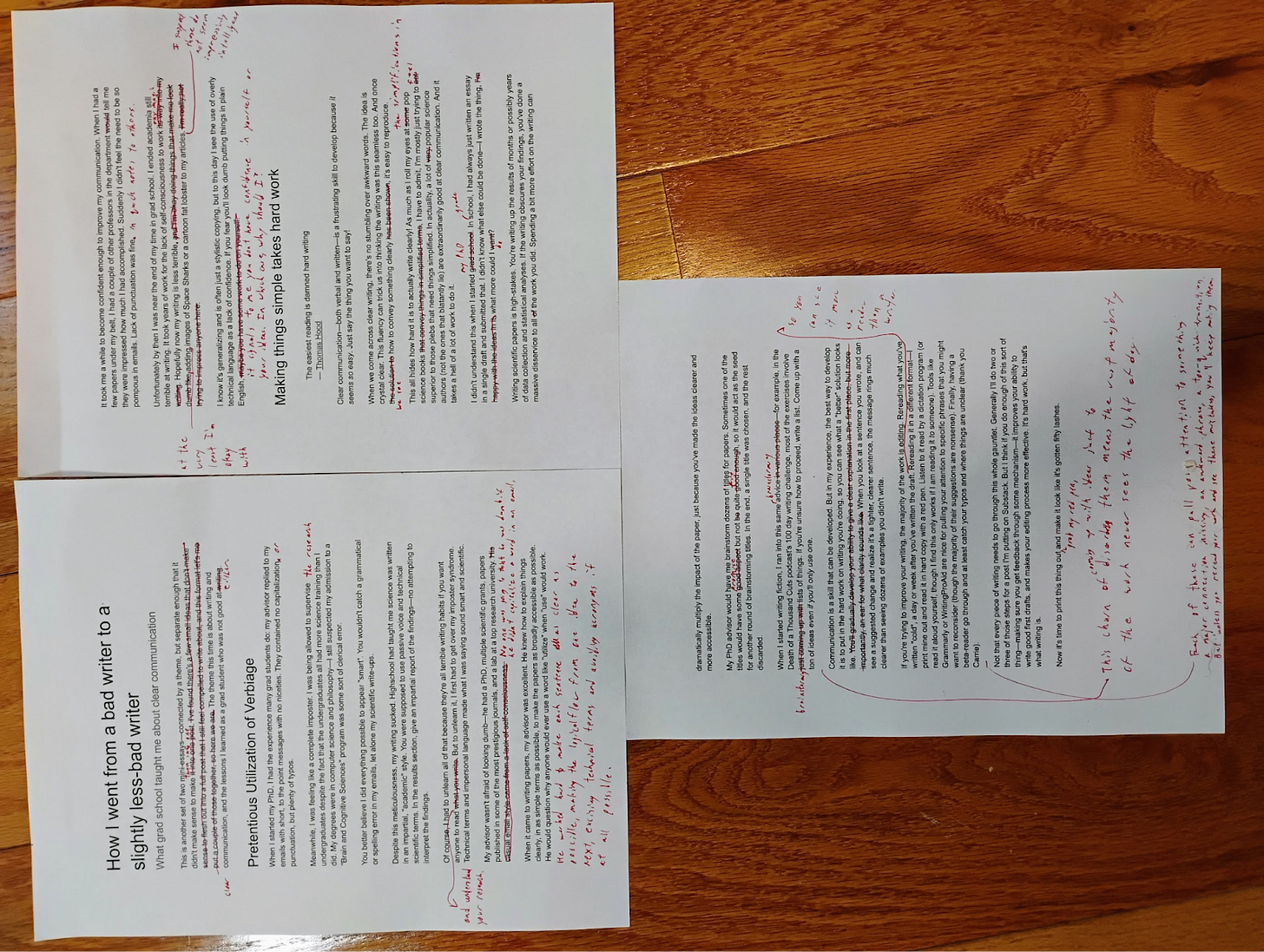

If you're trying to improve your writing, the majority of the work is editing: rereading what you've written "cold", a day or week after you've written the draft so you can see it more as a reader rather than a writer; rereading it in a different format—I print mine out and read it in hard copy with a red pen; listening to it read by a dictation program; using tools like Grammarly or WritingProAid to pull your attention to specific phrases that you might want to reconsider (though the majority of their suggestions are nonsense). Finally, having a beta-reader go through and at least catch your typos and where things are unclear (thank you

).Each of these steps can pull your attention to something. A major connection missing, an awkward phrase, a too-quick transition. Unless you reread your work and catch these, you'll never have the feedback necessary to stop making these mistakes.

Not that every piece of writing needs to go through this whole gauntlet. Generally I'll do two or three of those steps for a post I'm putting on Substack. But I think if you do enough of this sort of thing—making sure you get feedback through some mechanism—it improves your ability to write good first drafts, and makes your editing process more effective. It's hard work, but that's what writing is.

Now it's time to print this thing out, grab my red pen, and make it look like it's gotten fifty lashes.

Please hit the ❤️ “Like” button below if you enjoyed this post, it helps others find this article.

If you’re a Substack writer and have been enjoying Cognitive Wonderland, consider adding it to your recommendations. I really appreciate the support.

This is easy reading, like a knife through butter. I appreciate the damn hard work.

My general rule is if the jargon represents something specific, I will use it and explain it depending on my audience. New vocab represents compressions and abstractions of important ideas that might be totally unclaimed territory within someone's internal landscape. Using this language, we might hope to explaining something without brining in interpretive baggage.

I used to be on the opposite end of your imposture syndrome (still having it but expressed in a different way), totally afraid I might come off as pretentious. So I actually flaunted my bad spelling and grammar(in informal writing), and actively avoided any sophisticated-sounding words, not realizing how much this dampened me and also reduced specificity.

I read this somewhere that words are a way of representing complexity, and complexity is the intellectual's material in which they create new ideas. Maybe there is a golden mean, academics tend to overcomplicate, laymen tend to oversimplify. Much of the language used should depend on the goal is what I say. What's amazing is this oscillation between complexity and simplicity, how complexity can discover new things, and simplicity can make it easy to apply and understand(I strongly believe in Feynman's razor). So I think there is space for both.

Your editing advice is perfect though, and clarity is a goal no matter who the audience is.