Stroopid Intuitions

How Cognitive Conflict Fuels Philosophical Debate

Please hit the ❤️ “Like” button if you enjoy this post, it helps others find this article.

If (and likely only if) you've taken a cognitive psychology class, you've probably come across the name Stroop.

John Ridley Stroop was a psychology researcher who came up with one of the most famous results in cognitive psychology. Although his research was back in the 1930s, his name lives on in the Stroop Effect, which is constantly referenced and used in research to this day.

Despite producing some of the most influential cognitive psychology research, Stroop himself wasn't that interested in psychology. After publishing his dissertation and a couple of articles, he left experimental psychology, taking some teaching gigs but not publishing any more psychology research. His tiny body of research has still accrued a citation count of which most psychologists who devote their lives to research would be envious.

So what is it that Stroop showed?

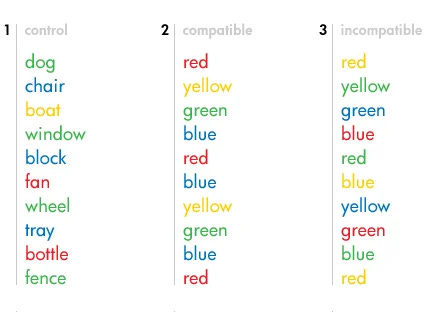

Here's a list of a few words. Try to name the color of the font.

If you're literate and don't have color blindness, you probably found the "control" words easy, the "compatible" ones even easier, and the "incompatible" ones… maybe not hard, but you were slower to do it. The word being in conflict with the color of the font makes it harder to name the color of the font.

The funny thing is this only happens when you're trying to name the color of the font. If I tell you to just read the words, the color of the font doesn't matter. There's a weird asymmetry here.

So that's the famous Stroop Effect. It's cool because it seems to tell us something about how the brain processes different kinds of visual stimuli (words versus colors). But what is it that it tells us?

There's multiple theories about what's going on in this weird little color naming task. But they all come down to some version of there being two processes, a color recognition process and a reading-the-word process, that occur in parallel. The output of those two processes compete in some way to enter some form of response selection process. Reading the word, for whatever reason, is processed faster or more automatically, which mucks up the process for response selection—when naming the font, we have to reject the wrong answer from our reading the word in addition to selecting the correct one. Processing the color of the font is either less automatic or slower, so we don't run into the same issue when just reading the word.

So the theories go. But the conflict between naming the ink color and reading a color name isn't the only kind of cognitive conflict researchers have studied.

What are clouds for?

Teleological reasoning is an annoyingly technical sounding term for "explaining stuff in terms of its purpose or goal". So if I say something like "Chairs exist to be sat upon", that's teleological reasoning. And in that case, it's true—chairs are generally made by people who intend for them to be sat upon.

Outside of human-made artifacts, where people have intentions and purposes, teleological reasoning gets, let's say, much more controversial. If I say something like "It rains so the flowers will get something to drink", this is again teleological reasoning. But, outside of a religious context (where you might see purpose in everything because God did it), this isn't true. Rain existed before flowers. Those flowering plants that could survive and best reproduce in an environment with rain stuck around and proliferated.

Perhaps an even more evocative example would be Douglas Adams's analogy of the puddle and the hole—a puddle looks around and realizes the hole that it's in fits it quite well, and decides the hole must have been made just for it. The puddle reasons the purpose of the hole must be to fit it.

But in this and many cases of erroneous teleological reasoning, this gets the cause backwards—the puddle fit to the hole, the hole wasn't made to fit the puddle.

The point is, teleological reasoning is appropriate in some cases (talking about the purpose of a human-made device, or why an animal has a specific appendage) and inappropriate in others (the purpose of an inanimate physical object).

Kids love teleological reasoning. Pre-schoolers tend to prefer and endorse teleological explanations for things—they seem to think everything, including natural objects like clouds, are for something. In one study, children explained certain rocks are pointy so animals won't sit on them. In another study, when shown a picture of a man and asked what the man is for, their most frequent response was "to walk around". This last result feels very poignant to me, as someone who paces a lot, and who has kids who are very aware that I pace a lot.

This reliance on teleological reasoning shifts over time, with older kids increasingly leaning towards more natural-mechanism based explanations (e.g. rocks are pointy because of physical processes like erosion). Adults tend to be okay with teleological reasoning for artifact parts (e.g. what is the handle of a mug for) or biological parts (e.g. what is the ear drum for), but not for natural objects (e.g. what is a cloud for).

At least, under normal circumstances.

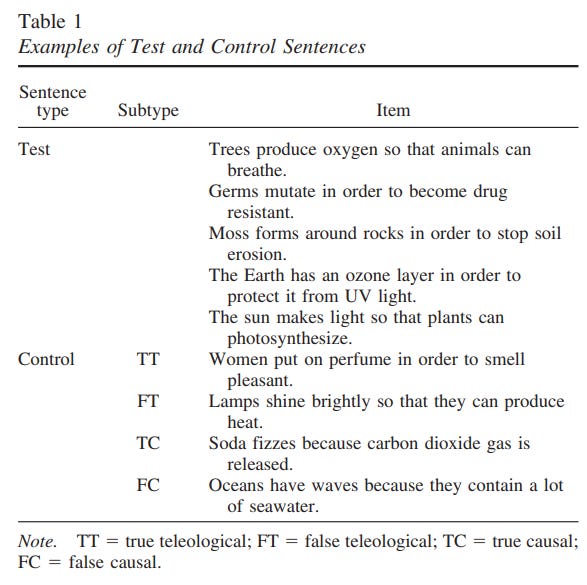

One study took professional physical scientists, the group you would think least likely to endorse teleological reasoning about physical things, and showed that under pressure they do resort to teleological reasoning. The study put scientists under time pressure, giving them 3.2 seconds to agree or disagree with different statements, some of which involved teleological reasoning. They found that, under time pressure, the rate of accepting teleological statements about natural things went up dramatically, while the rate of accepting "control" statements did not.

The authors conclude that teleological reasoning is a cognitive default. That is, even highly trained scientists continue to think in teleological terms about natural objects, but have learned to inhibit it. Much like the Stroop task, in which reading is faster or more automatic, the idea is teleological reasoning is faster or more automatic.

Whether you buy this conclusion or not (personally, I take it with a tentative grain of salt—it's a single study and there are other interpretations—maybe there are other reasons teleological-like statements take longer to think through), it's an interesting example of a deeper pattern: we often hold multiple contradictory ways of thinking about issues.

Clashing Intuitions

With both the Stroop task and the teleological reasoning study above, there is a clear "right" answer, even if the wrong answer also bubbles up from us. But sometimes, we have multiple different processes inside of us without a clear right or wrong answer.

I previously wrote about some of the psychology research on the trolley problem:

Imagine a trolley (I think that's British-talk for a streetcar) is barreling down a track towards five people who for some reason are tied to the track. The trolley will run over and kill those people. You are at a switch that would redirect the trolley, but it would redirect the trolley down another track where one person is tied up. Do you pull the switch?

A good portion of people say "Yes". One person dying isn't as bad as five.

Now consider a different scenario. The trolley is barreling down the track. You are standing on a footbridge above the track, next to a plump man who is leaning over the bridge for some reason. You could give the plump man a good shove and he would land on the track, and you're sure his heft would stop the trolley, again sacrificing one person to save five. Do you do it?

People have a different reaction to this version, generally being much more averse to shoving a person off the bridge than pulling the lever. But from a purely utilitarian perspective, this is hard to explain—the consequences seem the same between the two cases, sacrificing one life to save five.

Neuroscience research indicates different parts of our brain are active when we consider the two situations, suggesting we again have two different processes at work when considering these kinds of moral dilemmas.

There are plenty of other situations where we seem to have two different, contradictory processes at work when considering certain issues. Experimental philosophers have found that when it comes to moral responsibility, people are inconsistent in their judgements. If you ask people in the abstract whether they would consider people morally responsible for their actions in a deterministic universe, they say no. If you ask them to consider a specific case in a deterministic universe, they say yes. Similarly, researchers have suggested people have conflicting intuitions about perception.

People just seem to have different processes that come to opposing conclusions, even on philosophical questions.

Pumping Intuitions

Many philosophical thought experiments rely on the idea that people’s intuitions reveal something stable or revealing about morality or knowledge. But that premise is shaky. What we call “intuition” may just be the output of whichever internal process got to the finish line first—often from a jumble of contradictory mechanisms that respond differently depending on how the question is framed.

Daniel Dennett coined the term intuition pump for thought experiments that are meant to prime a particular view of an issue, designed to elicit specific intuitions by having you focus on certain aspects of a problem (at the expense of others). Though they have their uses, we have to be careful with intuition pumps because they might just elicit certain intuitions that rely on a specific framing.

Dennett suggests testing a thought experiment by “turning the knobs”—changing its details to see if your intuition holds. Take the trolley problem: pull a lever to save five, and it feels fine. But change one knob—now you're pushing someone off a bridge—and your gut response shifts. Same math, different story, all because we've shifted the emphasis of one little detail. That’s the danger of intuition pumps: they can manufacture conviction by sharpening certain features and smoothing out the rest.

More generally, for any given contentious philosophical topic, there is going to be a framing that makes any particular perspective feel intuitive—if not, I suspect no one would hold that position. Focusing on some aspect of the problem will make some conceptions feel more natural and some conclusions more fluid.

Many philosophical debates aren’t about the deep structure of the universe—they’re about us. About how our minds work. And when our intuitions clash, it’s not always because we’ve hit a paradox out in the world. Sometimes, just like with the Stroop Effect, we've just hit upon a conflict inside ourselves.

Please hit the ❤️ “Like” button below if you enjoyed this post, it helps others find this article.

If you’re a Substack writer and have been enjoying Cognitive Wonderland, consider adding it to your recommendations. I really appreciate the support.

I just realised I think there might be something else going on in the trolley problem. Like Mary's Room, and other intuition pumps, I think we cannot ignore the "realistic" approach to the problem. Thought experiment land should at least try to mimic reality. As such, for example, an ordinary person living in a black and white room does not know what black and white looks like, because they experience no lack of colour, as you or I would, if we entered the room. Without understanding this basic fact, it's hard to navigate the rest of the problem.

If we treat the trolley problem similarly, I would be very hesitant to push the fat dude over the track. Am I willing to kill a person with a plan that might not even work, and six people end up being killed? Of course I'm hesitant! Like wtf it's VERY different from the switch which is guaranteed to save 5 people. While this point may seem dumb, I think such subconscious awareness of the very dubious plan makes a huge difference for our "intuitions"?

In the switch situation, it's also unclear why the lone person is strapped to the track (is he really innocent?) and if he'll actually be set free to a beautiful future.

Again, might sound dumb, but I think these things are important background factors.

We now live in an environment where Trump and his minions are constantly "turning the knob" and it's driving us all bat shit crazy.